Sunday, March 7, 2021

FOR MY AUNT - by Angie M Flores

WHAT "MOTHER" MEANS - by Karl Fuchs

|

Thursday, March 4, 2021

THE DARLING - by ANTON P. CHEKOV

Olenka, the daughter

of the retired collegiate assessor Plemyanikov, was sitting on the back

door steps of her house doing nothing. It was hot, the flies were

nagging and teasing, and it was pleasant to think that it would soon be

evening. Dark rain clouds were gathering from the east, wafting a breath

of moisture every now and then.

Kukin, who roomed in

the wing of the same house, was standing in the yard looking up at the

sky. He was the manager of the Tivoli, an open-air theatre.

“Again,” he said

despairingly. “Rain again. Rain, rain, rain! Every day rain! As though

to spite me. I might as well stick my head into a noose and be done with

it. It’s ruining me. Heavy losses every day!” He wrung his hands, and

continued, addressing Olenka: “What a life, Olga Semyonovna! It’s enough

to make a man weep. He works, he does his best, his very best, he

tortures himself, he passes sleepless nights, he thinks and thinks and

thinks how to do everything just right. And what’s the result? He gives

the public the best operetta, the very best pantomime, excellent

artists. But do they want it? Have they the least appreciation of it?

The public is rude. The public is a great boor. The public wants a

circus, a lot of nonsense, a lot of stuff. And there’s the weather.

Look! Rain almost every evening. It began to rain on the tenth of May,

and it’s kept it up through the whole of June. It’s simply awful. I

can’t get any audiences, and don’t I have to pay rent? Don’t I have to

pay the actors?”

The next day towards evening the clouds gathered again, and Kukin said with an hysterical laugh:

“Oh, I don’t care.

Let it do its worst. Let it drown the whole theatre, and me, too. All

right, no luck for me in this world or the next. Let the actors bring

suit against me and drag me to court. What’s the court? Why not Siberia

at hard labour, or even the scaffold? Ha, ha, ha!”

It was the same on the third day.

Olenka listened to

Kukin seriously, in silence. Sometimes tears would rise to her eyes. At

last Kukin’s misfortune touched her. She fell in love with him. He was

short, gaunt, with a yellow face, and curly hair combed back from his

forehead, and a thin tenor voice. His features puckered all up when he

spoke. Despair was ever inscribed on his face. And yet he awakened in

Olenka a sincere, deep feeling.

She was always

loving somebody. She couldn’t get on without loving somebody. She had

loved her sick father, who sat the whole time in his armchair in a

darkened room, breathing heavily. She had loved her aunt, who came from

Brianska once or twice a year to visit them. And before that, when a

pupil at the progymnasium, she had loved her French teacher. She was a

quiet, kind-hearted, compassionate girl, with a soft gentle way about

her. And she made a very healthy, wholesome impression. Looking at her

full, rosy cheeks, at her soft white neck with the black mole, and at

the good naïve smile that always played on her face when something

pleasant was said, the men would think, “Not so bad,” and would smile

too; and the lady visitors, in the middle of the conversation, would

suddenly grasp her hand and exclaim, “You darling!” in a burst of

delight.

The house, hers by

inheritance, in which she had lived from birth, was located at the

outskirts of the city on the Gypsy Road, not far from the Tivoli. From

early evening till late at night she could hear the music in the theatre

and the bursting of the rockets; and it seemed to her that Kukin was

roaring and battling with his fate and taking his chief enemy, the

indifferent public, by assault. Her heart melted softly, she felt no

desire to sleep, and when Kukin returned home towards morning, she

tapped on her window-pane, and through the curtains he saw her face and

one shoulder and the kind smile she gave him.

He proposed to her,

and they were married. And when he had a good look of her neck and her

full vigorous shoulders, he clapped his hands and said:

“You darling!”

He was happy. But it rained on their wedding-day, and the expression of despair never left his face.

They got along well

together. She sat in the cashier’s box, kept the theatre in order, wrote

down the expenses, and paid out the salaries. Her rosy cheeks, her kind

naïve smile, like a halo around her face, could be seen at the

cashier’s window, behind the scenes, and in the café. She began to tell

her friends that the theatre was the greatest, the most important, the

most essential thing in the world, that it was the only place to obtain

true enjoyment in and become humanised and educated.

“But do you suppose

the public appreciates it?” she asked. “What the public wants is the

circus. Yesterday Vanichka and I gave Faust Burlesqued, and almost all

the boxes were empty. If we had given some silly nonsense, I assure you,

the theatre would have been overcrowded. To-morrow we’ll put Orpheus in

Hades on. Do come.”

Whatever Kukin said

about the theatre and the actors, she repeated. She spoke, as he did,

with contempt of the public, of its indifference to art, of its

boorishness. She meddled in the rehearsals, corrected the actors,

watched the conduct of the musicians; and when an unfavourable criticism

appeared in the local paper, she wept and went to the editor to argue

with him.

The actors were fond

of her and called her “Vanichka and I” and “the darling.” She was sorry

for them and lent them small sums. When they bilked her, she never

complained to her husband; at the utmost she shed a few tears.

In winter, too, they

got along nicely together. They leased a theatre in the town for the

whole winter and sublet it for short periods to a Little Russian

theatrical company, to a conjuror and to the local amateur players.

Olenka grew fuller

and was always beaming with contentment; while Kukin grew thinner and

yellower and complained of his terrible losses, though he did fairly

well the whole winter. At night he coughed, and she gave him raspberry

syrup and lime water, rubbed him with eau de Cologne, and wrapped him up

in soft coverings.

“You are my precious sweet,” she said with perfect sincerity, stroking his hair. “You are such a dear.”

At Lent he went to

Moscow to get his company together, and, while without him, Olenka was

unable to sleep. She sat at the window the whole time, gazing at the

stars. She likened herself to the hens that are also uneasy and unable

to sleep when their rooster is out of the coop. Kukin was detained in

Moscow. He wrote he would be back during Easter Week, and in his letters

discussed arrangements already for the Tivoli. But late one night,

before Easter Monday, there was an ill-omened knocking at the

wicket-gate. It was like a knocking on a barrel—boom, boom, boom! The

sleepy cook ran barefooted, plashing through the puddles, to open the

gate.

“Open the gate, please,” said some one in a hollow bass voice. “I have a telegram for you.”

Olenka had received

telegrams from her husband before; but this time, somehow, she was

numbed with terror. She opened the telegram with trembling hands and

read:

“Ivan Petrovich died suddenly to-day. Awaiting propt orders for wuneral Tuesday.”

That was the way the

telegram was written—“wuneral”—and another unintelligible word—“propt.”

The telegram was signed by the manager of the opera company.

“My dearest!” Olenka

burst out sobbing. “Vanichka, my dearest, my sweetheart. Why did I ever

meet you? Why did I ever get to know you and love you? To whom have you

abandoned your poor Olenka, your poor, unhappy Olenka?”

Kukin was buried on

Tuesday in the Vagankov Cemetery in Moscow. Olenka returned home on

Wednesday; and as soon as she entered her house she threw herself on her

bed and broke into such loud sobbing that she could be heard in the

street and in the neighbouring yards.

“The darling!” said the neighbours, crossing themselves. “How Olga Semyonovna, the poor darling, is grieving!”

Three months

afterwards Olenka was returning home from mass, downhearted and in deep

mourning. Beside her walked a man also returning from church, Vasily

Pustovalov, the manager of the merchant Babakayev’s lumber-yard. He was

wearing a straw hat, a white vest with a gold chain, and looked more

like a landowner than a business man.

“Everything has its

ordained course, Olga Semyonovna,” he said sedately, with sympathy in

his voice. “And if any one near and dear to us dies, then it means it

was God’s will and we should remember that and bear it with submission.”

He took her to the

wicket-gate, said good-bye and went away. After that she heard his

sedate voice the whole day; and on closing her eyes she instantly had a

vision of his dark beard. She took a great liking to him. And evidently

he had been impressed by her, too; for, not long after, an elderly

woman, a distant acquaintance, came in to have a cup of coffee with her.

As soon as the woman was seated at table she began to speak about

Pustovalov—how good he was, what a steady man, and any woman could be

glad to get him as a husband. Three days later Pustovalov himself paid

Olenka a visit. He stayed only about ten minutes, and spoke little, but

Olenka fell in love with him, fell in love so desperately that she did

not sleep the whole night and burned as with fever. In the morning she

sent for the elderly woman. Soon after, Olenka and Pustovalov were

engaged, and the wedding followed.

Pustovalov and

Olenka lived happily together. He usually stayed in the lumber-yard

until dinner, then went out on business. In his absence Olenka took his

place in the office until evening, attending to the book-keeping and

despatching the orders.

“Lumber rises twenty

per cent every year nowadays,” she told her customers and

acquaintances. “Imagine, we used to buy wood from our forests here. Now

Vasichka has to go every year to the government of Mogilev to get wood.

And what a tax!” she exclaimed, covering her cheeks with her hands in

terror. “What a tax!”

She felt as if she

had been dealing in lumber for ever so long, that the most important and

essential thing in life was lumber. There was something touching and

endearing in the way she pronounced the words, “beam,” “joist,” “plank,”

“stave,” “lath,” “gun-carriage,” “clamp.” At night she dreamed of whole

mountains of boards and planks, long, endless rows of wagons conveying

the wood somewhere, far, far from the city. She dreamed that a whole

regiment of beams, 36 ft. x 5 in., were advancing in an upright position

to do battle against the lumber-yard; that the beams and joists and

clamps were knocking against each other, emitting the sharp crackling

reports of dry wood, that they were all falling and then rising again,

piling on top of each other. Olenka cried out in her sleep, and

Pustovalov said to her gently:

“Olenka my dear, what is the matter? Cross yourself.”

Her husband’s

opinions were all hers. If he thought the room was too hot, she thought

so too. If he thought business was dull, she thought business was dull.

Pustovalov was not fond of amusements and stayed home on holidays; she

did the same.

“You are always either at home or in the office,” said her friends. “Why don’t you go to the theatre or to the circus, darling?”

“Vasichka and I

never go to the theatre,” she answered sedately. “We have work to do, we

have no time for nonsense. What does one get out of going to theatre?”

On Saturdays she and

Pustovalov went to vespers, and on holidays to early mass. On returning

home they walked side by side with rapt faces, an agreeable smell

emanating from both of them and her silk dress rustling pleasantly. At

home they drank tea with milk-bread and various jams, and then ate pie.

Every day at noontime there was an appetising odour in the yard and

outside the gate of cabbage soup, roast mutton, or duck; and, on fast

days, of fish. You couldn’t pass the gate without being seized by an

acute desire to eat. The samovar was always boiling on the office table,

and customers were treated to tea and biscuits. Once a week the married

couple went to the baths and returned with red faces, walking side by

side.

“We are getting

along very well, thank God,” said Olenka to her friends. “God grant that

all should live as well as Vasichka and I.”

When Pustovalov went

to the government of Mogilev to buy wood, she was dreadfully homesick

for him, did not sleep nights, and cried. Sometimes the veterinary

surgeon of the regiment, Smirnov, a young man who lodged in the wing of

her house, came to see her evenings. He related incidents, or they

played cards together. This distracted her. The most interesting of his

stories were those of his own life. He was married and had a son; but he

had separated from his wife because she had deceived him, and now he

hated her and sent her forty rubles a month for his son’s support.

Olenka sighed, shook her head, and was sorry for him.

“Well, the Lord keep

you,” she said, as she saw him off to the door by candlelight. “Thank

you for coming to kill time with me. May God give you health. Mother in

Heaven!” She spoke very sedately, very judiciously, imitating her

husband. The veterinary surgeon had disappeared behind the door when she

called out after him: “Do you know, Vladimir Platonych, you ought to

make up with your wife. Forgive her, if only for the sake of your son.

The child understands everything, you may be sure.”

When Pustovalov

returned, she told him in a low voice about the veterinary surgeon and

his unhappy family life; and they sighed and shook their heads, and

talked about the boy who must be homesick for his father. Then, by a

strange association of ideas, they both stopped before the sacred

images, made genuflections, and prayed to God to send them children.

And so the

Pustovalovs lived for full six years, quietly and peaceably, in perfect

love and harmony. But once in the winter Vasily Andreyich, after

drinking some hot tea, went out into the lumber-yard without a hat on

his head, caught a cold and took sick. He was treated by the best

physicians, but the malady progressed, and he died after an illness of

four months. Olenka was again left a widow.

“To whom have you

left me, my darling?” she wailed after the funeral. “How shall I live

now without you, wretched creature that I am. Pity me, good people, pity

me, fatherless and motherless, all alone in the world!”

She went about

dressed in black and weepers, and she gave up wearing hats and gloves

for good. She hardly left the house except to go to church and to visit

her husband’s grave. She almost led the life of a nun.

It was not until six

months had passed that she took off the weepers and opened her

shutters. She began to go out occasionally in the morning to market with

her cook. But how she lived at home and what went on there, could only

be surmised. It could be surmised from the fact that she was seen in her

little garden drinking tea with the veterinarian while he read the

paper out loud to her, and also from the fact that once on meeting an

acquaintance at the post-office, she said to her:

“There is no proper

veterinary inspection in our town. That is why there is so much disease.

You constantly hear of people getting sick from the milk and becoming

infected by the horses and cows. The health of domestic animals ought

really to be looked after as much as that of human beings.”

She repeated the

veterinarian’s words and held the same opinions as he about everything.

It was plain that she could not exist a single year without an

attachment, and she found her new happiness in the wing of her house. In

any one else this would have been condemned; but no one could think ill

of Olenka. Everything in her life was so transparent. She and the

veterinary surgeon never spoke about the change in their relations. They

tried, in fact, to conceal it, but unsuccessfully; for Olenka could

have no secrets. When the surgeon’s colleagues from the regiment came to

see him, she poured tea, and served the supper, and talked to them

about the cattle plague, the foot and mouth disease, and the municipal

slaughter houses. The surgeon was dreadfully embarrassed, and after the

visitors had left, he caught her hand and hissed angrily:

“Didn’t I ask you

not to talk about what you don’t understand? When we doctors discuss

things, please don’t mix in. It’s getting to be a nuisance.”

She looked at him in astonishment and alarm, and asked:

“But, Volodichka, what am I to talk about?”

And she threw her arms round his neck, with tears in her eyes, and begged him not to be angry. And they were both happy.

But their happiness

was of short duration. The veterinary surgeon went away with his

regiment to be gone for good, when it was transferred to some distant

place almost as far as Siberia, and Olenka was left alone.

Now she was

completely alone. Her father had long been dead, and his armchair lay in

the attic covered with dust and minus one leg. She got thin and homely,

and the people who met her on the street no longer looked at her as

they had used to, nor smiled at her. Evidently her best years were over,

past and gone, and a new, dubious life was to begin which it were

better not to think about.

In the evening

Olenka sat on the steps and heard the music playing and the rockets

bursting in the Tivoli; but it no longer aroused any response in her.

She looked listlessly into the yard, thought of nothing, wanted nothing,

and when night came on, she went to bed and dreamed of nothing but the

empty yard. She ate and drank as though by compulsion.

And what was worst

of all, she no longer held any opinions. She saw and understood

everything that went on around her, but she could not form an opinion

about it. She knew of nothing to talk about. And how dreadful not to

have opinions! For instance, you see a bottle, or you see that it is

raining, or you see a muzhik riding by in a wagon. But what the bottle

or the rain or the muzhik are for, or what the sense of them all is, you

cannot tell—you cannot tell, not for a thousand rubles. In the days of

Kukin and Pustovalov and then of the veterinary surgeon, Olenka had had

an explanation for everything, and would have given her opinion freely

no matter about what. But now there was the same emptiness in her heart

and brain as in her yard. It was as galling and bitter as a taste of

wormwood.

Gradually the town

grew up all around. The Gypsy Road had become a street, and where the

Tivoli and the lumber-yard had been, there were now houses and a row of

side streets. How quickly time flies! Olenka’s house turned gloomy, the

roof rusty, the shed slanting. Dock and thistles overgrew the yard.

Olenka herself had aged and grown homely. In the summer she sat on the

steps, and her soul was empty and dreary and bitter. When she caught the

breath of spring, or when the wind wafted the chime of the cathedral

bells, a sudden flood of memories would pour over her, her heart would

expand with a tender warmth, and the tears would stream down her cheeks.

But that lasted only a moment. Then would come emptiness again, and the

feeling, What is the use of living? The black kitten Bryska rubbed up

against her and purred softly, but the little creature’s caresses left

Olenka untouched. That was not what she needed. What she needed was a

love that would absorb her whole being, her reason, her whole soul, that

would give her ideas, an object in life, that would warm her aging

blood. And she shook the black kitten off her skirt angrily, saying:

“Go away! What are you doing here?”

And so day after day, year after year not a single joy, not a single opinion. Whatever Marva, the cook, said was all right.

One hot day in July,

towards evening, as the town cattle were being driven by, and the whole

yard was filled with clouds of dust, there was suddenly a knocking at

the gate. Olenka herself went to open it, and was dumbfounded to behold

the veterinarian Smirnov. He had turned grey and was dressed as a

civilian. All the old memories flooded into her soul, she could not

restrain herself, she burst out crying, and laid her head on Smirnov’s

breast without saying a word. So overcome was she that she was totally

unconscious of how they walked into the house and seated themselves to

drink tea.

“My darling!” she murmured, trembling with joy. “Vladimir Platonych, from where has God sent you?”

“I want to settle

here for good,” he told her. “I have resigned my position and have come

here to try my fortune as a free man and lead a settled life. Besides,

it’s time to send my boy to the gymnasium. He is grown up now. You know,

my wife and I have become reconciled.”

“Where is she?” asked Olenka.

“At the hotel with the boy. I am looking for lodgings.”

“Good gracious,

bless you, take my house. Why won’t my house do? Oh, dear! Why, I won’t

ask any rent of you,” Olenka burst out in the greatest excitement, and

began to cry again. “You live here, and the wing will be enough for me.

Oh, Heavens, what a joy!”

The very next day

the roof was being painted and the walls whitewashed, and Olenka, arms

akimbo, was going about the yard superintending. Her face brightened

with her old smile. Her whole being revived and freshened, as though she

had awakened from a long sleep. The veterinarian’s wife and child

arrived. She was a thin, plain woman, with a crabbed expression. The boy

Sasha, small for his ten years of age, was a chubby child, with clear

blue eyes and dimples in his cheeks. He made for the kitten the instant

he entered the yard, and the place rang with his happy laughter.

“Is that your cat, auntie?” he asked Olenka. “When she has little kitties, please give me one. Mamma is awfully afraid of mice.”

Olenka chatted with

him, gave him tea, and there was a sudden warmth in her bosom and a soft

gripping at her heart, as though the boy were her own son.

In the evening, when he sat in the dining-room studying his lessons, she looked at him tenderly and whispered to herself:

“My darling, my pretty. You are such a clever child, so good to look at.”

“An island is a tract of land entirely surrounded by water,” he recited.

“An island is a

tract of land,” she repeated—the first idea asseverated with conviction

after so many years of silence and mental emptiness.

She now had her

opinions, and at supper discussed with Sasha’s parents how difficult the

studies had become for the children at the gymnasium, but how, after

all, a classical education was better than a commercial course, because

when you graduated from the gymnasium then the road was open to you for

any career at all. If you chose to, you could become a doctor, or, if

you wanted to, you could become an engineer.

Sasha began to go to

the gymnasium. His mother left on a visit to her sister in Kharkov and

never came back. The father was away every day inspecting cattle, and

sometimes was gone three whole days at a time, so that Sasha, it seemed

to Olenka, was utterly abandoned, was treated as if he were quite

superfluous, and must be dying of hunger. So she transferred him into

the wing along with herself and fixed up a little room for him there.

Every morning Olenka

would come into his room and find him sound asleep with his hand tucked

under his cheek, so quiet that he seemed not to be breathing. What a

shame to have to wake him, she thought.

“Sashenka,” she said sorrowingly, “get up, darling. It’s time to go to the gymnasium.”

He got up, dressed,

said his prayers, then sat down to drink tea. He drank three glasses of

tea, ate two large cracknels and half a buttered roll. The sleep was not

yet out of him, so he was a little cross.

“You don’t know your

fable as you should, Sashenka,” said Olenka, looking at him as though

he were departing on a long journey. “What a lot of trouble you are. You

must try hard and learn, dear, and mind your teachers.”

“Oh, let me alone, please,” said Sasha.

Then he went down

the street to the gymnasium, a little fellow wearing a large cap and

carrying a satchel on his back. Olenka followed him noiselessly.

“Sashenka,” she called.

He looked round and

she shoved a date or a caramel into his hand. When he reached the street

of the gymnasium, he turned around and said, ashamed of being followed

by a tall, stout woman:

“You had better go home, aunt. I can go the rest of the way myself.”

She stopped and stared after him until he had disappeared into the school entrance.

Oh, how she loved

him! Not one of her other ties had been so deep. Never before had she

given herself so completely, so disinterestedly, so cheerfully as now

that her maternal instincts were all aroused. For this boy, who was not

hers, for the dimples in his cheeks and for his big cap, she would have

given her life, given it with joy and with tears of rapture. Why? Ah,

indeed, why?

When she had seen

Sasha off to the gymnasium, she returned home quietly, content, serene,

overflowing with love. Her face, which had grown younger in the last

half year, smiled and beamed. People who met her were pleased as they

looked at her.

“How are you, Olga Semyonovna, darling? How are you getting on, darling?”

“The gymnasium

course is very hard nowadays,” she told at the market. “It’s no joke.

Yesterday the first class had a fable to learn by heart, a Latin

translation, and a problem. How is a little fellow to do all that?”

And she spoke of the teacher and the lessons and the text-books, repeating exactly what Sasha said about them.

At three o’clock

they had dinner. In the evening they prepared the lessons together, and

Olenka wept with Sasha over the difficulties. When she put him to bed,

she lingered a long time making the sign of the cross over him and

muttering a prayer. And when she lay in bed, she dreamed of the

far-away, misty future when Sasha would finish his studies and become a

doctor or an engineer, have a large house of his own, with horses and a

carriage, marry and have children. She would fall asleep still thinking

of the same things, and tears would roll down her cheeks from her closed

eyes. And the black cat would lie at her side purring: “Mrr, mrr, mrr.”

Suddenly there was a

loud knocking at the gate. Olenka woke up breathless with fright, her

heart beating violently. Half a minute later there was another knock.

“A telegram from

Kharkov,” she thought, her whole body in a tremble. “His mother wants

Sasha to come to her in Kharkov. Oh, great God!”

She was in despair.

Her head, her feet, her hands turned cold. There was no unhappier

creature in the world, she felt. But another minute passed, she heard

voices. It was the veterinarian coming home from the club.

“Thank God,” she

thought. The load gradually fell from her heart, she was at ease again.

And she went back to bed, thinking of Sasha who lay fast asleep in the

next room and sometimes cried out in his sleep:

“I’ll give it to you! Get away! Quit your scrapping!”

Wednesday, March 3, 2021

THE OAK - by Alfred Lord Tennyson

Friday, February 26, 2021

THE CHIEF MATE - by James Russell Lowell

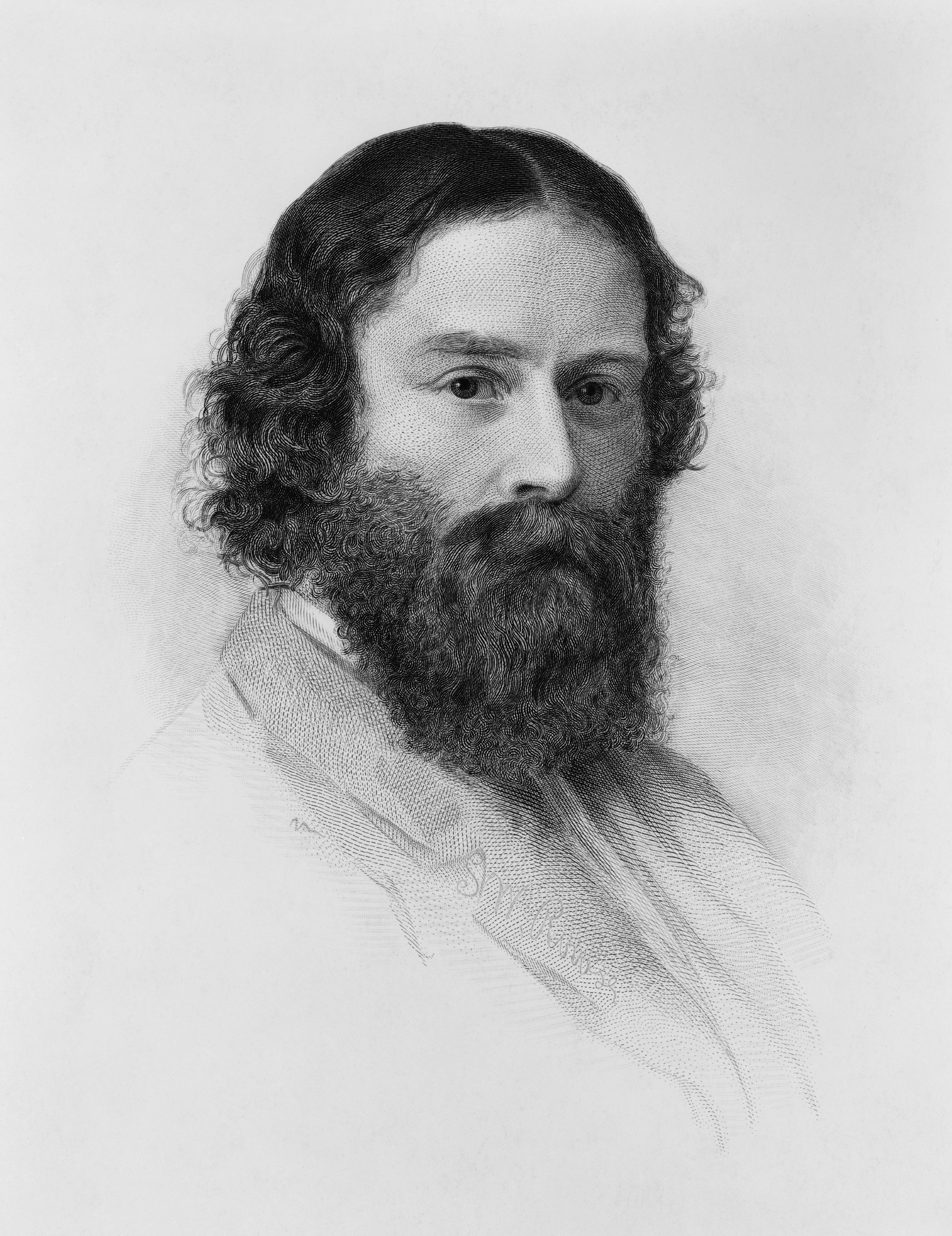

James

Russell Lowell ( 1819 – 1891) was an American Romantic poet, critic,

editor, and diplomat. He is associated with the Fireside Poets, a group

of New England writers who were among the first American poets that

rivaled the popularity of British poets. These writers usually used

conventional forms and meters in their poetry, making them suitable for

families entertaining at their fireside.

THE CHIEF MATE

My

first glimpse of Europe was the shore of Spain. Since we got into the

Mediterranean, we have been becalmed for some days within easy view of

it. All along are fine mountains, brown all day, and with a bloom on

them at sunset like that of a ripe plum. Here and there at their feet

little white towns are sprinkled along the edge of the water, like the

grains of rice dropped by the princess in the story. Sometimes we see

larger buildings on the mountain slopes, probably convents. I sit and

wonder whether the farther peaks may not be the Sierra Morena (the rusty

saw) of Don Quixote. I resolve that they shall be, and am content.

Surely latitude and longitude never showed me any particular respect,

that I should be over scrupulous with them.

But

after all, Nature, though she may be more beautiful, is nowhere so

entertaining as in man, and the best thing I have seen and learned at

sea is our Chief Mate. My first acquaintance with him was made over my

knife, which he asked to look at, and, after a critical examination,

handed back to me, saying, "I shouldn't wonder if that 'ere was a good

piece o' stuff." Since then he has transferred a part of his regard for

my knife to its owner. I like folks who like an honest bit of steel, and

take no interest whatever in "your Raphaels, Correggios, and stuff."

There is always more than the average human nature in the man who has a

hearty sympathy with iron. It is a manly metal, with no sordid

associations like gold and silver. My sailor fully came up to my

expectation on further acquaintance. He might well be called an old salt

who had been wrecked on Spitzbergen before I was born. He was not an

American, but I should never have guessed it by his speech, which was

the purest Cape Cod, and I reckon myself a good taster of dialects. Nor

was he less Americanized in all his thoughts and feelings, a singular

proof of the ease with which our omnivorous country assimilates foreign

matter, provided it be Protestant, for he was a man ere he became an

American citizen. He used to walk the deck with his hands in his

pockets, in seeming abstraction, but nothing escaped his eyes. How he

saw I could never make out, though I had a theory that it was with his

elbows. After he had taken me (or my knife) into his confidence, he took

care that I should see whatever he deemed of interest to a landsman.

Without looking up, he would say, suddenly, "There's a whale blowin'

clearn up to win'ard," or, "Them's porpises to leeward: that means

change o' wind." He is as impervious to cold as a polar bear, and paces

the deck during his watch much as one of those yellow hummocks goes

slumping up and down his cage. On the Atlantic, if the wind blew a gale

from the northeast, and it was cold as an English summer, he was sure to

turn out in a calico shirt and trousers, his furzy brown chest half

bare, and slippers, without stockings. But lest you might fancy this to

have chanced by defect of wardrobe, he comes out in a monstrous

pea-jacket here in the Mediterranean, when the evening is so hot that

Adam would have been glad to leave off his fig-leaves. "It's a kind o'

damp and unwholesome in these ere waters," he says, evidently regarding

the Midland Sea as a vile standing pool, in comparison with the bluff

ocean. At meals he is superb, not only for his strengths, but his

weaknesses. He has somehow or other come to think me a wag, and if I ask

him to pass the butter, detects an occult joke, and laughs as much as

is proper for a mate. For you must know that our social hierarchy on

shipboard is precise, and the second mate, were he present, would only

laugh half as much as the first. Mr. X. always combs his hair, and works

himself into a black frock coat (on Sundays he adds a waist coat)

before he comes to meals, sacrificing himself nobly and painfully to the

social proprieties. The second mate, on the other hand, who eats after

us, enjoys the privilege of shirt-sleeves, and is, I think, the happier

man of the two. We do not have seats above and below the salt, as in old

time, but above and below the white sugar. Mr. X. always takes brown

sugar, and it is delightful to see how he ignores the existence of

certain delicates which he considers above his grade, tipping his head

on one side with an air of abstraction so that he may seem not to deny

himself, but to omit helping himself from inadvertence, or absence of

mind. At such times he wrinkles his forehead in a peculiar manner,

inscrutable at first as a cuneiform inscription, but as easily read

after you once get the key. The sense of it is something like this: "I,

X., know my place, a height of wisdom attained by few. Whatever you may

think, I do not see that currant jelly, nor that preserved grape.

Especially a kind Providence has made me blind to bowls of white sugar,

and deaf to the pop of champagne corks. It is much that a merciful

compensation gives me a sense of the dingier hue of Havana, and the

muddier gurgle of beer. Are there potted meats? My physician has ordered

me three pounds of minced salt-junk at every meal." There is such a

thing, you know, as a ship's husband: X. is the ship's poor relation.

As

I have said, he takes also a below-the-white-sugar interest in the

jokes, laughing by precise point of compass, just as he would lay the

ship's course, all yawing being out of the question with his scrupulous

decorum at the helm. Once or twice I have got the better of him, and

touched him off into a kind of compromised explosion, like that of damp

fireworks, that splutter and simmer a little, and then go out with

painful slowness and occasional relapses. But his fuse is always of the

unwillingest, and you must blow your match, and touch him off again and

again with the same joke. Or rather, you must magnetize him many times

to get him en rapport with a jest. This once accomplished, you have him,

and one bit of fun will last the whole voyage. He prefers those of one

syllable, the a-b abs of humor. The gradual fattening of the steward, a

benevolent mulatto with whiskers and earrings, who looks as if he had

been meant for a woman, and had become a man by accident, as in some of

those stories by the elder physiologists, is an abiding topic of

humorous comment with Mr. X. "That 'ere stooard," he says, with a brown

grin like what you might fancy on the face of a serious and aged seal,

"'s agittin' as fat's a porpis. He was as thin's a shingle when he come

aboord last v'yge. Them trousis'll bust yit. He don't darst take 'em off

nights, for the whole ship's company couldn't git him into 'em agin."

And then he turns aside to enjoy the intensity of his emotion by

himself, and you hear at intervals low rumblings, an indigestion of

laughter. He tells me of St. Elmo's fires, Marvell's corposants, though

with him the original corpos santos has suffered a sea change, and

turned to comepleasants, pledges of fine weather. I shall not soon find a

pleasanter companion. It is so delightful to meet a man who knows just

what you do not. Nay, I think the tired mind finds something in plump

ignorance like what the body feels in cushiony moss. Talk of the

sympathy of kindred pursuits! It is the sympathy of the upper and nether

mill-stones, both forever grinding the same grist, and wearing each

other smooth. One has not far to seek for book-nature, artist-nature,

every variety of superinduced nature, in short, but genuine human-nature

is hard to find. And how good it is! Wholesome as a potato, fit company

for any dish. The free masonry of cultivated men is agreeable, but

artificial, and I like better the natural grip with which manhood

recognizes manhood.

X.

has one good story, and with that I leave him, wishing him with all my

heart that little inland farm at last which is his calenture as he paces

the windy deck. One evening, when the clouds looked wild and whirling, I

asked X. if it was coming on to blow. "No, I guess not," said he;

"bumby the moon'll be up, and scoff away that 'ere loose stuff." His

intonation set the phrase "scoff away" in quotation-marks as plain as

print. So I put a query in each eye, and he went on. "Ther' was a Dutch

cappen onct, an' his mate come to him in the cabin, where he sot takin'

his schnapps, an' says, 'Cappen, it's agittin' thick, an' looks kin' o'

squally, hedn't we's good's shorten sail?' 'Gimmy my alminick,' says the

cappen. So he looks at it a spell, an' says he, 'The moon's due in

less'n half an hour, an' she'll scoff away ev'ythin' clare agin.' So the

mate he goes, an' bumby down he comes agin, an' says, 'Cappen, this

'ere's the allfiredest, powerfullest moon 't ever you did see. She's

scoffed away the main-togallants'l, an' she's to work on the foretops'l

now. Guess you'd better look in the alminick agin, and fin' out when

this moon sets.' So the cappen thought 'twas 'bout time to go on deck.

Dreadful slow them Dutch cappens be." And X. walked away, rumbling

inwardly, like the rote of the sea heard afar.

Wednesday, February 24, 2021

WITCH AND WITCHCRAFT - by Prabir Gayen

|

I OPENED A BOOK - by Julia Donaldson

| |

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)