Sunday, January 31, 2021

POEMS FOR CHILDREN - Verse by W · A · FRISBIE - 1901

A FIRE IN FROGTOWN

One sultry night in Frogtown

The muskrats’ house caught fire;

The muskrats, with their babies,

Rushed out in scant attire.

Then all the Frogtown firemen,

In startled haste arose,

And ran to put the fire out

With dandelion hose.

THE PORCUPINE’S DILEMMA

A porcupine once played at golf

And wore a sweater red.

“I notice all the swells dress so.

“And so will I”, he said.

But when he found his stylish clothes

Were far too warm for golf,

His sharp quills held that sweater fast

He couldn’t get it off.

A monkey, sitting on a tree

Above a shady pool,

Looked down and saw a crocodile

Within the water cool.

The crocodile looked up and said,

“Come down my friend and swim.”

Intending, when the monkey came,

To make a meal of him.

The monkey knew this was his plan

But leaped as if to dive.

The crocodile spread wide his jaws

To catch his meal alive;

But he was disappointed much

To see his sharp game fail

For, as he leaped, the monkey caught

And hung there by his tail.

One beast there is which should be shunned

By little girls and boys;

That is the cross Whine-os-ce-ros,

Which makes an awful noise.

For if they see this animal

And do not run away,

They imitate its shrill, harsh voice

And whine the livelong day.

THE PROUD WISHBONE

The wishbone was a haughty thing

And high he held his head;

The Wing twins were but “common trash,”

And Drumsticks too, he said.

“It’s just as plain as anything

“That this is so,” quoth he,

“For there are two of each of them

“But only one of Me.”

And when two children at the feast

Each for the wishbone cried

The Wishbone said “I told you so”

And oh, he swelled with pride.

They took him each one by a foot

As children often do,

Then each one gave a sudden tug

And broke him right in two.

There was a dancing camel with a desert caravan;

His driver was a busy and an un-esthetic man,

Who made the camel work all day and gave him ne’er a chance

To lay his heavy load aside and do a fancy dance.

But when they reached a city and heard street musicians play,

The camel danced a step or two while jogging on his way,

And quickly people thronged about to wonder and to stare,

While the driver passed the hat and made his fortune then and there.

Young George Augustus William Bubb

Was far too dignified

To play at games like other boys

They grated on his pride.

He did not know how kites are made,

Nor how to play at ball,

Nor how to skate, nor how to swim,

Nor anything at all.

Said Mrs. Robin breathlessly

“The frosts are nearly due,

This moving south is troublesome,

The baggage heavy, too.”

Said Mr. Rob, “Oh, that’s all right,

We’ll bill the baggage through.”

Wednesday, January 27, 2021

CARNIVAL OF BLACK AND WHITE IN COLOMBIA - TRAVEL

From 2 to 7 January in the Colombian city of Pasto, a colorful carnival "Black and White" (Carnaval Negros y Blancos) takes place. The history of the carnival began in the 17th century, when African slaves demanded a free day from the Spanish colonialists for fun and relaxation. Over time, the carnival has become a large-scale celebration symbolizing human equality and the unity of cultures. On festive days, there are a number of entertainment events, several concerts and a solemn procession of funny papier-mâché dolls. The holiday ends with a grand gastronomic fair of local dishes and products.

Thursday, January 21, 2021

DIVORCE - by Jackie Kay

| |

Monday, January 18, 2021

LOVE - by Chris Farmer

FOR YOU ARE THE ONE - by Chris Messick

|

Friday, January 15, 2021

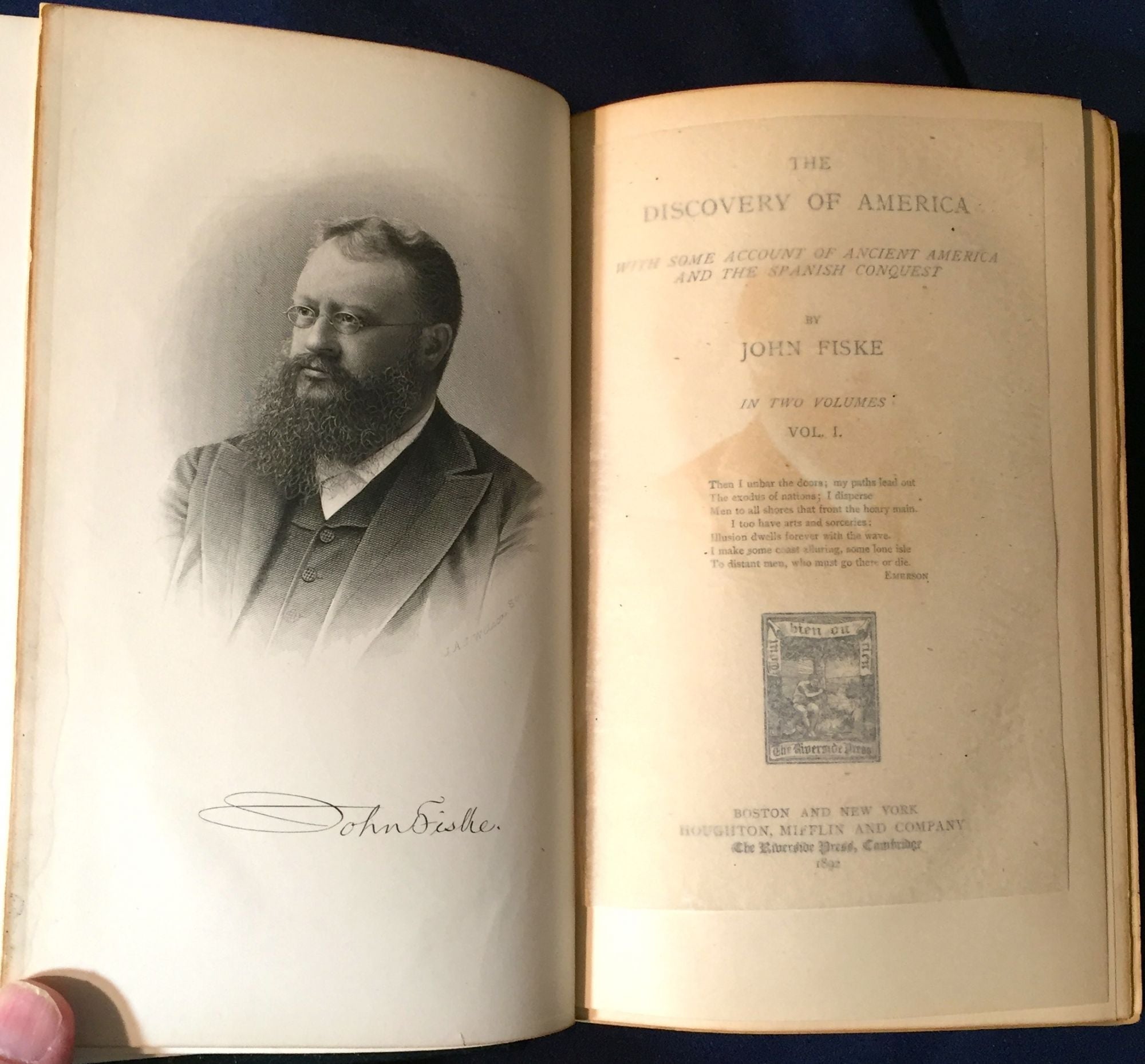

THE PART PLAYED BY INFANCY IN THE EVOLUTION OF MAN - by John Fiske

When Darwin's

“Origin of Species” was first published, when it gave us that wonderful

explanation of the origin of forms of life from allied forms through the

operation of natural selection, it must have been like a mental

illumination to every person who comprehended it. But after all it left a

great many questions unexplained, as was natural. It accounted for the

phenomena of organic development in general with wonderful success, but

it must have left a great many minds with the feeling: If man has been

produced in this way, if the mere operation of natural selection has

produced the human race, wherein is the human race anyway essentially

different from lower races? Is not man really dethroned, taken down from

that exceptional position in which we have been accustomed to place

him, and might it not be possible, in the course of the future, for

other beings to come upon the earth as far superior to man as man is

superior to the fossilized dragons of Jurassic antiquity?

Such questions used

to be asked, and when they were asked, although one might have a very

strong feeling that it was not so, at the same time one could not

exactly say why. One could not then find any scientific argument for

objections to that point of view. But with the further development of

the question the whole subject began gradually to wear a different

appearance; and I am going to give you a little bit of autobiography,

because I think it may be of some interest in this connection. I am

going to mention two or three of the successive stages which the whole

question took in my own mind as one thing came up after another, and how

from time to time it began to dawn upon me that I had up to that point

been looking at the problem from not exactly the right point of view.

When Darwin's

“Descent of Man” was published in 1871, it was of course a book

characterized by all his immense learning, his wonderful fairness of

spirit and fertility of suggestion. Still, one could not but feel that

it did not solve the question of the origin of man. There was one great

contrast between that book and his “Origin of Species.” In the earlier

treatise he undertook to point out a vera causa (true cause) of the

origin of species, and he did it. In his “Descent of Man” he brought

together a great many minor generalizations which facilitated the

understanding of man's origin. But he did not come at all near to

solving the central problem, nor did he anywhere show clearly why the

natural selection might not have gone on forever producing one set of

beings after another distinguishable chiefly by physical differences.

But Darwin's co-discoverer, Alfred Russel Wallace, at an early stage in

his researches, struck out a most brilliant and pregnant suggestion. In

that one respect Wallace went further than ever Darwin did. It was a

point of which, indeed, Darwin admitted the importance. It was a point

of which nobody could fail to understand the importance, that in the

course of the evolution of a very highly organized animal, if there came

a point at which it was of more advantage to that animal to have

variations in his intelligence seized upon and improved by natural

selection than to have physical changes seized upon, then natural

selection would begin working almost exclusively upon that creature's

intelligence, and he would develop in intelligence to a great extent,

while his physical organism would change but slightly. Now, that of

course applied to the case of man, who is changed physically but very

slightly from the apes, while he has traversed intellectually such a

stupendous chasm.

As soon as this

statement was made by Wallace, it seemed to me to open up an entirely

new world of speculation. There was this enormous antiquity of man,

during the greater part of which he did not know enough to make history.

We see man existing here on the earth, no one can say how long, but

surely many hundreds of thousands of years, yet only during just the

last little fringe of four or five thousand years has he arrived at the

point where he makes history. Before that, something was going on, a

great many things were going on, while his ancestors were slowly growing

up to that point of intelligence where it began to make itself felt in

the recording of events. This agrees with Wallace's suggestion of a long

period of psychical change, accompanied by slight physical change.

Well, in the spring

of 1871, when Darwin's “Descent of Man” came out, just about the same

time I happened to be reading Wallace's account of his experiences in

the Malay Archipelago, and how at one time he caught a female

orang-outang with a new-born baby, and the mother died, and Wallace

brought up the baby orang-outang by hand; and this baby orang-outang had

a kind of infancy which was a great deal longer than that of a cow or a

sheep, but it was nothing compared to human infancy in length. This

little orang-outang could not get up and march around, as mammals of

less intelligence do, when he was first born, or within three or four

days; but after three or four weeks or so he would get up, and begin

taking hold of something and pushing it around, just as children push a

chair; and he went through a period of staring at his hands, as human

babies do, and altogether was a good deal slower in getting to the point

where he could take care of himself. And while I was reading of that I

thought, Dear me! if there is any one thing in which the human race is

signally distinguished from other mammals, it is in the enormous

duration of their infancy; but it is a point that I do not recollect

ever seeing any naturalist so much as allude to.

It happened at just

that time that I was making researches in psychology about the

organization of experiences, the way in which conscious intelligent

action can pass down into quasi-automatic action, the generation of

instincts, and various allied questions; and I thought, Can it be that

the increase of intelligence in an animal, if carried beyond a certain

point, must necessarily result in prolongation of the period of infancy,

must necessarily result in the birth of the mammal at a less developed

stage, leaving something to be done, leaving a good deal to be done,

after birth? And then the argument seemed to come along very naturally,

that for every action of life, every adjustment which a creature makes

in life, whether a muscular adjustment or an intelligent adjustment,

there has got to be some registration effected in the nervous system,

some line of transit worn for nervous force to follow; there has got to

be a connection between certain nerve-centres before the thing can be

done, whether it is the acts of the viscera or the acts of the limbs, or

anything of that sort; and of course it is obvious that if the creature

has not many things to register in his nervous system, if he has a life

which is very simple, consisting of few actions that are performed with

great frequency, that animal becomes almost automatic in his whole

life; and all the nervous connections that need to be made to enable him

to carry on life get made during the fœtal period [the period before

birth] or during the egg period, and when he comes to be born, he comes

all ready to go to work. As one result of this, he does not learn from

individual experience, but one generation is like the preceding

generations, with here and there some slight modifications. But when you

get the creature that has arrived at the point where his experience has

become varied, he has got to do a good many things, and there is more

or less individuality about them; and many of them are not performed

with the same minuteness and regularity, so that there does not begin to

be that automatism within the period during which he is being developed

and his form is taking on its outlines. During prenatal life (before

birth) there is not time enough for all these nervous registrations, and

so by degrees it comes about that he is born with his nervous system

perfectly capable only of making him breathe and digest food, of making

him do the things absolutely requisite for supporting life; instead of

being born with a certain number of definite developed capacities, he

has a number of potentialities which have got to be roused according to

his own individual experience. Pursuing that line of thought, it began

after a while to seem clear to me that the infancy of the animal in a

very undeveloped condition, with the larger part of his faculties in

potentiality rather than in actuality, was a direct result of the

increase of intelligence, and I began to see that now we have two steps:

first, natural selection goes on increasing the intelligence; and

secondly, when the intelligence goes far enough, it makes a longer

infancy, a creature is born less developed, and therefore there comes

this plastic period during which he is more teachable. The capacity for

progress begins to come in, and you begin to get at one of the great

points in which man is distinguished from the lower animals, for one of

those points is undoubtedly his progressiveness; and I think that any

one will say, with very little hesitation, that if it were not for our

period of infancy we should not be progressive. If we came into the

world with our capacities all cut and dried, one generation would be

very much like another.

Then, looking around

to see what are the other points which are most important in which man

differs from the lower animals, there comes that matter of the family.

The family has adumbrations and foreshadowings among the lower animals,

but in general it may be said that while mammals lower than man are

gregarious, in man have become established those peculiar relationships

which constitute what we know as the family; and it is easy to see how

the existence of helpless infants would bring about just that state of

things. The necessity of caring for the infants would prolong the period

of maternal affection, and would tend to keep the father and mother and

children together, but it would tend especially to keep the mother and

children together. This business of the marital relations was not really

a thing that became adjusted in the primitive ages of man, but it has

become adjusted in the course of civilization. Real monogamy, real

faithfulness of the male parent, belongs to a comparatively advanced

stage; but in the earlier stages the knitting together of permanent

relations between mother and infant, and the approximation toward steady

relations on the part of the male parent, came to bring about the

family and gradually to knit those organizations which we know as clans.

Here we come to

another stage, another step forward. The instant society becomes

organized in clans, natural selection cannot let these clans be broken

up and die out, the clan becomes the chief object or care of natural

selection, because, if you destroy it you retrograde again, you lose all

you have gained; consequently, those clans in which the primeval

selfish instincts were so modified that the individual conduct would be

subordinated to some extent to the needs to the clan, those are the ones

which would prevail in the struggle for life. In this way you gradually

get an external standard to which man has to conform his conduct, and

you get the germs of altruism and morality; and in the prolonged

affectionate relation between the mother and the infant you get the

opportunity for that development of altruistic feeling which, once

started in those relations, comes into play in the more general

relations, and makes more feasible and more workable the bonds which

keep society together, and enable it to unite on wider and wider terms.

So it seems that

from a very small beginning we are reaching a very considerable result. I

had got these facts pretty clearly worked out, and carried them around

with me some years, before a fresh conclusion came over me one day with a

feeling of surprise. In the old days before the Copernican astronomy

was promulgated, man regarded himself as the centre of the universe. He

used to entertain theological systems which conformed to his limited

knowledge of nature. The universe seemed to be made for his uses, the

earth seemed to have been fitted up for his dwelling-place, he occupied

the centre of creation, the sun was made to give him light, etc. When

Copernicus overthrew that view, the effect upon theology was certainly

tremendous. I do not believe that justice has ever been done to the

shock that it gave to man when he was made to realize that he occupied a

kind of miserable little clod of dirt in the universe, and that there

were so many other worlds greater than this. It was one of the first

great shocks involved in the change from ancient to modern scientific

views, and I do not doubt it was responsible for a great deal of the

pessimistic philosophizing that came in the seventeenth and eighteenth

centuries.

Now, it flashed upon

me a dozen years or so ago after thinking about this manner in which

man originated that man occupies certainly just as exceptional a

position as before, if he is the terminal in a long series of

evolutionary events. If at the end of the long history of evolution

comes man, if this whole secular process has been going on to produce

this supreme object, it does not much matter what kind of a cosmical

body he lives on. He is put back into the old position of theological

importance, and in a much more intelligent way than in the old days when

he was supposed to occupy the centre of the universe. We are enabled to

say that while there is no doubt of the evolutionary process going on

through countless ages which we know nothing about, yet in the one case

where it is brought home to us we spell out an intelligible story, and

we do find things working along up to man as a terminal fact in the

whole process. This is indeed a consistent conclusion from Wallace's

suggestion that natural selection, in working toward the genesis of man,

began to follow a new path and make psychical changes instead of

physical changes. Obviously, here you are started upon a new chapter in

the history of the universe. It is no longer going to be necessary to

shape new limbs, and to thicken the skin and make new growths of hair,

when man has learned how to build a fire, when he can take some other

animal's hide and make it into clothes. You have got to a new state of

things.

After I had put

together all these additional circumstances with regard to the

origination of human society and the development of altruism, I began to

see a little further into the matter. It then began to appear that not

only is man the terminal factor in a long process of evolution, but in

the origination of man there began the development of the higher

psychical attributes, and those attributes are coming to play a greater

and greater part in the development of the human race. Just take this

mere matter of “altruism,” as we call it. It is not a pretty word, but

must serve for want of a better. In the development of altruism from the

low point, where there was scarcely enough to hold the clan together,

up to the point reached at the present day, there has been a notable

progress, but there is still room for an enormous amount of improvement.

The progress has been all in the direction of bringing out what we call

the higher spiritual attributes. The feeling was now more strongly

impressed upon me than ever, that all these things tended to set the

whole doctrine of evolution into harmony with religion; that if the past

through which man had originated was such as has been described, then

religion was a fit and worthy occupation for man, and some of the

assumptions which underlie every system of religion must be true. For

example, with regard to the assumption that what we see of the present

life is not the whole thing; that there is a spiritual side of the

question beside the material side; that, in short, there is for man a

life eternal. When I wrote the “Destiny of Man,” all that I ventured to

say was, that it did not seem quite compatible with ordinary common

sense to suppose that so much pains would have been taken to produce a

merely ephemeral result. But since then another argument has occurred to

me: that just at the time when the human race was beginning to come

upon the scene, when the germs of morality were coming in with the

family, when society was taking its first start, there came into the

human mind, how one can hardly say, but there did come, the beginnings

of a groping after something that lies outside and beyond the world of

sense. That groping after a spiritual world has been going on here for

much more than a hundred thousand years, and it has played an enormous

part in the history of mankind, in the whole development of human

society. Nobody can imagine what mankind would have been without it up

to the present time. Either all religion has been a reaching out for a

phantom that does not exist, or a reaching out after something that does

exist, but of which man, with his limited intelligence, has only been

able to gain a crude idea. And the latter seems a far more probable

conclusion, because, if it is not so, it constitutes a unique exception

to all the operations of evolution we know about. As a general thing in

the whole history of evolution, when you see any internal adjustment

reaching out toward something, it is in order to adapt itself to

something that really exists; and if the religious cravings of man

constitute an exception, they are the one thing in the whole process of

evolution that is exceptional and different from all the rest. And this

is surely an argument of stupendous and resistless weight.

I take this

autobiographical way of referring to these things, in the order in which

they came before my mind, for the sake of illustration. The net result

of the whole is to put evolution in harmony with religious thought, not

necessarily in harmony with particular religious dogmas or theories, but

in harmony with the great religious drift, so that the antagonism which

used to appear to exist between religion and science is likely to

disappear. So I think it will before a great while. If you take the case

of some evolutionist like Professor Haeckel, who is perfectly sure that

materialism accounts for everything (he has got it all cut and dried

and settled; he knows all about it, so that there is really no need of

discussing the subject!); if you ask the question whether it was his

scientific study of evolution that really led him to such a dogmatic

conclusion, or whether it was that he started from some purely arbitrary

assumption, like the French materialists of the eighteenth century, I

have no doubt that the latter would be the true explanation. There are a

good many people who start on their theories of evolution with these

ultimate questions all settled to begin with. It was the most natural

thing in the world that after the first assaults of science upon old

beliefs, after a certain number of Bible stories and a certain number of

church doctrines had been discredited, there should be a school of men

who in sheer weariness should settle down to scientific researches, and

say, “We content ourselves with what we can prove by the methods of

physical science, and we will throw everything else overboard.” That was

very much the state of mind of the famous French atheists of the last

century. But only think how chaotic nature was to their minds compared

to what she is to our minds today. Just think how we have in the present

century arrived where we can see the bearings of one set of facts in

nature as collated with another set of facts, and contrast it with the

view which even the greatest of those scientific French materialists

could take. Consider how fragmentary and how lacking in arrangement was

the universe they saw compared with the universe we see today, and it is

not strange that to them it could be an atheistic world. That hostility

between science and religion continued as long as religion was linked

hand in hand with the ancient doctrine of special creation. But now that

the religious world has unmoored itself, now that it is beginning to

see the truth and beauty of natural science and to look with friendship

upon conceptions of evolution, I suspect that this temporary antagonism,

which we have fallen into a careless way of regarding as an everlasting

antagonism, will come to an end perhaps quicker than we realize.

There is one point

that is of great interest in this connection, although I can only hint

at it. Among the things that happened in that dim past when man was

coming into existence was the increase of his powers of manipulation;

and that was a factor of immense importance. Anaxagoras, it is said,

wrote a treatise in which he maintained that the human race would never

have become human if it had not been for the hand. I do not know that

there was so very much exaggeration about that. It was certainly of

great significance that the particular race of mammals whose

intelligence increased far enough to make it worth while for natural

selection to work upon intelligence alone was the race which had

developed hands and could manipulate things. It was a wonderful era in

the history of creation when that creature could take a club and use it

for a hammer, or could pry up a stone with a stake, thus adding one more

lever to the levers that made up his arm. From that day to this, the

career of man has been that of a person who has operated upon his

environment in a different way from any animal before him. An era of

similar importance came probably somewhat later, when man learned how to

build a fire and cook his food. Here was another means of acting upon

the environment. Here was the beginning of the working of endless

physical and chemical changes through the application of heat, just as

the first use of the club or the crowbar was the beginning of an

enormous development in the mechanical arts.

Now, at the same

time, to go back once more into that dim past, when ethics and religion,

manual art and scientific thought, found expression in the crudest form

of myths, the æsthetic sense was germinating likewise. Away back in the

glacial period you find pictures drawn and scratched upon the

reindeer's antler, portraitures of mammoths and primitive pictures of

the chase; you see the trinkets, the personal decorations, proving

beyond question that the æsthetic sense was there. There has been an

immense aesthetic development since then. And I believe that in the

future it is going to mean far more to us than we have yet begun to

realize. I refer to the kind of training that comes to mankind through

direct operation upon his environment, the incarnation of his thought,

the putting of his ideas into new material relations. This is going to

exert powerful effects of a civilizing kind. There is something strongly

educational and disciplinary in the mere dealing with matter, whether

it be in the manual training-school, whether it be in carpentry, in

overcoming the inherent and total depravity of inanimate things, shaping

them to your will, and also in learning to subject yourself to their

will (for sometimes you must do that in order to achieve your conquests;

in other words, you must humour their habits and proclivities). In all

this there is a priceless discipline, moral as well as mental, let alone

the fact that, in whatever kind of artistic work a man does, he is

doing that which in the very working has in it an element of something

outside of egoism; even if he is doing it for motives not very

altruistic, he is working toward a result the end of which is the

gratification or the benefit of other persons than himself; he is

working toward some result which in a measure depends upon their

approval, and to that extent tends to bring him into closer relations to

his fellow man.

In the future, to an

even greater extent than in the recent past, crude labour will be

replaced by mechanical contrivances. The kind of labour which can

command its price is the kind which has trained intelligence behind it.

One of the great needs of our time is the multiplication of skilled and

special labour. The demand for the products of intelligence is far

greater than that for mere crude products of labour, and it will be more

and more so. For there comes a time when the latter products have

satisfied the limit to which a man can consume food and drink and

shelter, those things which merely keep the animal alive. But to those

things which minister to the requirements of the spiritual side of a man

there is almost no limit. The demand one can conceive is well-nigh

infinite. One of the philosophical things that have been said, in

discriminating man from the lower animals, is that he is the one

creature who is never satisfied. It is well for him that he is so, that

there is always something more for which he craves. To my mind this fact

most strongly hints that man is infinitely more than a mere animate

machine.

John

Fiske attained distinction in three distinct fields of letters: as a

historian, as a scientific interpreter of religion, as an expositor of

the philosophy of evolution. In this last department of his work his

original contribution was the theory here set forth, taken from a

chapter in “A Century of Science and Other Essays,”.

John Fiske (1842 – 1901) was an American philosopher and historian.

John

Fiske was born Edmund Fiske Green at Hartford, Connecticut, March 30,

1842. He was the only child of Edmund Brewster Green, of Smyrna,

Delaware, and Mary Fiske Bound, of Middletown, Connecticut. His father

was editor of newspapers in Hartford, New York City, and Panama, where

he died in 1852, and his widow married Edwin W. Stoughton, of New York,

in 1855. On the second marriage of his mother, Edmund Fiske Green

assumed the name of his maternal great-grandfather, John Fiske.

As

a child, Fiske exhibited remarkable precocity. He lived at Middletown

during childhood, until he entered Harvard. He graduated from Harvard

College in 1863 and from Harvard Law School in 1865. He had already

admitted to the Suffolk bar in 1864, but never practised law. His career

as author began in 1861, with an article on "Mr. Buckle's Fallacies"

published in the National Quarterly Review. After that, he was a

frequent contributor to American and British periodicals.

From

1869 to 1871, he was university lecturer on philosophy at Harvard, in

1870 instructor in history there, and assistant librarian 1872-1879. On

resigning the latter position in 1879, he was elected a member of the

board of overseers, and at the expiration of the six-years' term was

re-elected in 1885. Beginning in 1881, he lectured annually on American

history at Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri, and beginning in

1884 held a professorship of American history at that institution, but

continued to make his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He lectured on

American history at University College London in 1879, and at the Royal

Institution of Great Britain in 1880. He gave many hundreds of lectures,

chiefly upon American history, in the principal cities of the United

States and Great Britain. Fiske was elected a member of the American

Antiquarian Society in 1884.

The

largest part of his life was devoted to the study of history, but at an

early age inquiries into the nature of human progress led him to a

careful study of the doctrine of evolution, and it was through the

popularization of Charles Darwin's work that he first became known to

the public. He applied himself to the philosophical interpretation of

Darwin's work and produced many books and essays on this subject. His

philosophy was influenced by Herbert Spencer's views on evolution. In a

letter from Charles Darwin to John Fiske, dated from 1874, the

naturalist remarks: "I never in my life read so lucid an expositor (and

therefore thinker) as you are."

Nineteenth-century

enthusiasm for brain size as a simple measure of human performance,

championed by scientists including Darwin's cousin Francis Galton and

the French neurologist Paul Broca, led Fiske to believe in the racial

superiority of the "Anglo-Saxon race". Fiske's beliefs on race did not

preclude his commitment to abolitionist causes. Indeed, so anti-slavery

was he that twenty-three years after the cessation of the American Civil

War, he declared the North's victory complete "despite the feeble

wails" of "unteachable bigots." In his book "The Destiny of Man" (1884),

he devotes a whole chapter to the "End of the working of natural

selection upon man", describing it as "a fact of unparalleled grandeur."

In his view, "the action of natural selection upon Man has [...] been

essentially diminished through the operation of social conditions."

In

books such as Outlines of Cosmic Philosophy, Fiske aimed to show that

"in reality there has never been any conflict between religion and

science, nor is any reconciliation called for where harmony has always

existed." On page 364, he demonstrates his sensitivity to Christianity

as a religion:

"We arrive at a deeper reason than has hitherto been disclosed for the

difference between our position with reference to Christianity, and that

which has been assumed by Radicalism and by Positivism. It is not

merely that we refuse to attack Christianity because we recognize its

necessary adaptation to a certain stage of culture, not yet passed by

the average minds of the community; it is that we still regard

Christianity as, in the deepest sense, our own religion."

Fiske

was a popular lecturer on these topics in his early career. Later he

turned to historical writings, publishing books such as The Discovery of

America (1892). In addition, he edited, with James Grant Wilson,

Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography (1887). He died, worn out by

overwork, at Gloucester, Massachusetts, July 4, 1901.

source for biography:

Thursday, January 14, 2021

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)