Monday, November 30, 2020

REASONS WHY - by Joanna Fuchs

Friday, November 27, 2020

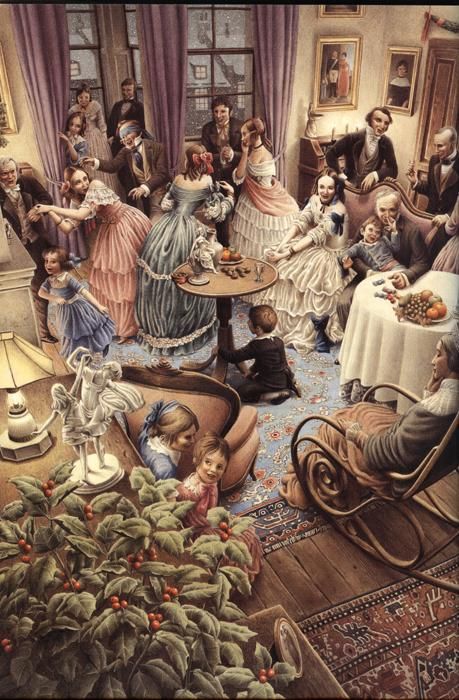

THE CHRISTMAS TREE AND THE WEDDING - by F. M. DOSTOYEVSKY

The other day I saw a

wedding... But no! I would rather tell you about a Christmas tree. The

wedding was superb. I liked it immensely. But the other incident was

still finer. I don’t know why it is that the sight of the wedding

reminded me of the Christmas tree. This is the way it happened:

Exactly five years

ago, on New Year’s Eve, I was invited to a children’s ball by a man high

up in the business world, who had his connections, his circle of

acquaintances, and his intrigues. So it seemed as though the children’s

ball was merely a pretext for the parents to come together and discuss

matters of interest to themselves, quite innocently and casually.

I was an outsider,

and, as I had no special matters to air, I was able to spend the evening

independently of the others. There was another gentleman present who

like myself had just stumbled upon this affair of domestic bliss. He was

the first to attract my attention. His appearance was not that of a man

of birth or high family. He was tall, rather thin, very serious, and

well dressed. Apparently he had no heart for the family festivities. The

instant he went off into a corner by himself the smile disappeared from

his face, and his thick dark brows knitted into a frown. He knew no one

except the host and showed every sign of being bored to death, though

bravely sustaining the role of thorough enjoyment to the end. Later I

learned that he was a provincial, had come to the capital on some

important, brain-racking business, had brought a letter of

recommendation to our host, and our host had taken him under his

protection, not at all con amore. It was merely out of politeness that

he had invited him to the children’s ball.

They did not play

cards with him, they did not offer him cigars. No one entered into

conversation with him. Possibly they recognised the bird by its feathers

from a distance. Thus, my gentleman, not knowing what to do with his

hands, was compelled to spend the evening stroking his whiskers. His

whiskers were really fine, but he stroked them so assiduously that one

got the feeling that the whiskers had come into the world first and

afterwards the man in order to stroke them.

There was another

guest who interested me. But he was of quite a different order. He was a

personage. They called him Julian Mastakovich. At first glance one

could tell he was an honoured guest and stood in the same relation to

the host as the host to the gentleman of the whiskers. The host and

hostess said no end of amiable things to him, were most attentive,

wining him, hovering over him, bringing guests up to be introduced, but

never leading him to any one else. I noticed tears glisten in our host’s

eyes when Julian Mastakovich remarked that he had rarely spent such a

pleasant evening. Somehow I began to feel uncomfortable in this

personage’s presence. So, after amusing myself with the children, five

of whom, remarkably well-fed young persons, were our host’s, I went into

a little sitting-room, entirely unoccupied, and seated myself at the

end that was a conservatory and took up almost half the room.

The children were

charming. They absolutely refused to resemble their elders,

notwithstanding the efforts of mothers and governesses. In a jiffy they

had denuded the Christmas tree down to the very last sweet and had

already succeeded in breaking half of their playthings before they even

found out which belonged to whom.

One of them was a

particularly handsome little lad, dark-eyed, curly-haired, who

stubbornly persisted in aiming at me with his wooden gun. But the child

that attracted the greatest attention was his sister, a girl of about

eleven, lovely as a Cupid. She was quiet and thoughtful, with large,

full, dreamy eyes. The children had somehow offended her, and she left

them and walked into the same room that I had withdrawn into. There she

seated herself with her doll in a corner.

“Her father is an

immensely wealthy business man,” the guests informed each other in tones

of awe. “Three hundred thousand rubles set aside for her dowry

already.”

As I turned to look

at the group from which I heard this news item issuing, my glance met

Julian Mastakovich’s. He stood listening to the insipid chatter in an

attitude of concentrated attention, with his hands behind his back and

his head inclined to one side.

All the while I was

quite lost in admiration of the shrewdness our host displayed in the

dispensing of the gifts. The little maid of the many-rubied dowry

received the handsomest doll, and the rest of the gifts were graded in

value according to the diminishing scale of the parents’ stations in

life. The last child, a tiny chap of ten, thin, red-haired, freckled,

came into possession of a small book of nature stories without

illustrations or even head and tail pieces. He was the governess’s

child. She was a poor widow, and her little boy, clad in a sorry-looking

little nankeen jacket, looked thoroughly crushed and intimidated. He

took the book of nature stories and circled slowly about the children’s

toys. He would have given anything to play with them. But he did not

dare to. You could tell he already knew his place.

I like to observe

children. It is fascinating to watch the individuality in them

struggling for self-assertion. I could see that the other children’s

things had tremendous charm for the red-haired boy, especially a toy

theatre, in which he was so anxious to take a part that he resolved to

fawn upon the other children. He smiled and began to play with them. His

one and only apple he handed over to a puffy urchin whose pockets were

already crammed with sweets, and he even carried another youngster

pickaback, all simply that he might be allowed to stay with the theatre.

But in a few moments

an impudent young person fell on him and gave him a pummelling. He did

not dare even to cry. The governess came and told him to leave off

interfering with the other children’s games, and he crept away to the

same room the little girl and I were in. She let him sit down beside

her, and the two set themselves busily dressing the expensive doll.

Almost half an hour

passed, and I was nearly dozing off, as I sat there in the conservatory

half listening to the chatter of the red haired boy and the dowered

beauty, when Julian Mastakovich entered suddenly. He had slipped out of

the drawing-room under cover of a noisy scene among the children. From

my secluded corner it had not escaped my notice that a few moments

before he had been eagerly conversing with the rich girl’s father, to

whom he had only just been introduced.

He stood still for a while reflecting and mumbling to himself, as if counting something on his fingers.

“Three hundred -

three hundred - eleven - twelve - thirteen - sixteen in five years!

Let’s say four per cent - five times twelve - sixty, and on these sixty.

Let us assume that in five years it will amount to well, four hundred.

Hm - hm! But the shrewd old fox isn’t likely to be satisfied with four

per cent. He gets eight or even ten, perhaps. Let’s suppose five

hundred, five hundred thousand, at least, that’s sure. Anything above

that for pocket money - hm...”

He blew his nose and

was about to leave the room when he spied the girl and stood still. I,

behind the plants, escaped his notice. He seemed to me to be quivering

with excitement. It must have been his calculations that upset him so.

He rubbed his hands and danced from place to place, and kept getting

more and more excited. Finally, however, he conquered his emotions and

came to a standstill. He cast a determined look at the future bride and

wanted to move toward her, but glanced about first. Then, as if with a

guilty conscience, he stepped over to the child on tip-toe, smiling, and

bent down and kissed her head.

His coming was so unexpected that she uttered a shriek of alarm.

“What are you doing here, dear child ?” he whispered, looking around and pinching her cheek.

“We’re playing.”

“What, with him?”

said Julian Mastakovich with a look askance at the governess’s child.

“You should go into the drawing-room, my lad,” he said to him.

The boy remained

silent and looked up at the man with wide-open eyes. Julian Mastakovich

glanced round again cautiously and bent down over the girl.

“What have you got, a doll, my dear?”

“Yes, sir.” The child quailed a little, and her brow wrinkled.

“A doll? And do you know, my dear, what dolls are made of?”

“No, sir,” she said weakly, and lowered her head.

“Out of rags, my

dear. You, boy, you go back to the drawing-room, to the children,” said

Julian Mastakovich looking at the boy sternly.

The two children frowned. They caught hold of each other and would not part.

“And do you know why they gave you the doll?” asked Julian Mastakovich, dropping his voice lower and lower.

“No.”

“Because you were a good, very good little girl the whole week.”

Saying which, Julian

Mastakovich was seized with a paroxysm of agitation. He looked round

and said in a tone faint, almost inaudible with excitement and

impatience:

“If I come to visit your parents will you love me, my dear?”

He tried to kiss the

sweet little creature, but the red-haired boy saw that she was on the

verge of tears, and he caught her hand and sobbed out loud in sympathy.

That enraged the man.

“Go away! Go away! Go back to the other room, to your playmates.”

“I don’t want him to. I don’t want him to! You go away!” cried the girl. “Let him alone! Let him alone!” She was almost weeping.

There was a sound of

footsteps in the doorway. Julian Mastakovich started and straightened

up his respectable body. The red-haired boy was even more alarmed. He

let go the girl’s hand, sidled along the wall, and escaped through the

drawing-room into the dining-room.

Not to attract

attention, Julian Mastakovich also made for the dining-room. He was red

as a lobster. The sight of himself in a mirror seemed to embarrass him.

Presumably he was annoyed at his own ardour and impatience. Without due

respect to his importance and dignity, his calculations had lured and

pricked him to the greedy eagerness of a boy, who makes straight for his

object - though this was not as yet an object; it only would be so in

five years’ time. I followed the worthy man into the dining-room, where I

witnessed a remarkable play.

Julian Mastakovich,

all flushed with vexation, venom in his look, began to threaten the

red-haired boy. The red-haired boy retreated farther and farther until

there was no place left for him to retreat to, and he did not know where

to turn in his fright.

“Get out of here!

What are you doing here? Get out, I say, you good-for-nothing! Stealing

fruit, are you? Oh, so, stealing fruit! Get out, you freckle face, go to

your likes!”

The frightened

child, as a last desperate resort, crawled quickly under the table. His

persecutor, completely infuriated, pulled out his large linen

handkerchief and used it as a lash to drive the boy out of his position.

Here I must remark

that Julian Mastakovich was a somewhat corpulent man, heavy, well-fed,

puffy-cheeked, with a paunch and ankles as round as nuts. He perspired

and puffed and panted. So strong was his dislike (or was it jealousy?)

of the child that he actually began to carry on like a madman.

I laughed heartily.

Julian Mastakovich turned. He was utterly confused and for a moment,

apparently, quite oblivious of his immense importance. At that moment

our host appeared in the doorway opposite. The boy crawled out from

under the table and wiped his knees and elbows. Julian Mastakovich

hastened to carry his handkerchief, which he had been dangling by the

corner, to his nose. Our host looked at the three of us rather

suspiciously. But, like a man who knows the world and can readily adjust

himself, he seized upon the opportunity to lay hold of his very

valuable guest and get what he wanted out of him.

“Here’s the boy I

was talking to you about,” he said, indicating the red-haired child. “I

took the liberty of presuming on your goodness in his behalf.”

“Oh,” replied Julian Mastakovich, still not quite master of himself.

“He’s my governess’s

son,” our host continued in a beseeching tone. “She’s a poor creature,

the widow of an honest official. That’s why, if it were possible for you

”

“Impossible,

impossible!” Julian Mastakovich cried hastily. “You must excuse me,

Philip Alexeyevich, I really cannot. I’ve made inquiries. There are no

vacancies, and there is a waiting list of ten who have a greater right ,

I’m sorry.”

“Too bad,” said our host. “He’s a quiet, unobtrusive child.”

“A very naughty

little rascal, I should say,” said Julian Mastakovich, wryly. “Go away,

boy. Why are you here still? Be off with you to the other children.”

Unable to control

himself, he gave me a sidelong glance. Nor could I control myself. I

laughed straight in his face. He turned away and asked our host, in

tones quite audible to me, who that odd young fellow was. They whispered

to each other and left the room, disregarding me.

I shook with

laughter. Then I, too, went to the drawing-room. There the great man,

already surrounded by the fathers and mothers and the host and the

hostess, had begun to talk eagerly with a lady to whom he had just been

introduced. The lady held the rich little girl’s hand. Julian

Mastakovich went into fulsome praise of her. He waxed ecstatic over the

dear child’s beauty, her talents, her grace, her excellent breeding,

plainly laying himself out to flatter the mother, who listened scarcely

able to restrain tears of joy, while the father showed his delight by a

gratified smile.

The joy was

contagious. Everybody shared in it. Even the children were obliged to

stop playing so as not to disturb the conversation. The atmosphere was

surcharged with awe. I heard the mother of the important little girl,

touched to her profoundest depths, ask Julian Mastakovich in the

choicest language of courtesy, whether he would honour them by coming to

see them. I heard Julian Mastakovich accept the invitation with

unfeigned enthusiasm. Then the guests scattered decorously to different

parts of the room, and I heard them, with veneration in their tones,

extol the business man, the business man’s wife, the business man’s

daughter, and, especially, Julian Mastakovich.

“Is he married?” I asked out loud of an acquaintance of mine standing beside Julian Mastakovich.

Julian Mastakovich gave me a venomous look.

“No,” answered my acquaintance, profoundly shocked by my - intentional - indiscretion.

***

Not long ago I

passed the Church of ---. I was struck by the concourse of people

gathered there to witness a wedding. It was a dreary day. A drizzling

rain was beginning to come down. I made my way through the throng into

the church. The bridegroom was a round, well-fed, pot-bellied little

man, very much dressed up. He ran and fussed about and gave orders and

arranged things. Finally word was passed that the bride was coming. I

pushed through the crowd, and I beheld a marvellous beauty whose first

spring was scarcely commencing. But the beauty was pale and sad. She

looked distracted. It seemed to me even that her eyes were red from

recent weeping. The classic severity of every line of her face imparted a

peculiar significance and solemnity to her beauty. But through that

severity and solemnity, through the sadness, shone the innocence of a

child. There was something inexpressibly naive, unsettled and young in

her features, which, without words, seemed to plead for mercy.

They said she was

just sixteen years old. I looked at the bridegroom carefully. Suddenly I

recognised Julian Mastakovich, whom I had not seen again in all those

five years. Then I looked at the bride again. - Good God! I made my way,

as quickly as I could, out of the church. I heard gossiping in the

crowd about the bride’s wealth about her dowry of five hundred thousand

rubles so and so much for pocket money.

“Then his calculations were correct,” I thought, as I pressed out into the street.

Thursday, November 26, 2020

Wednesday, November 25, 2020

BULGARIAN PAINTER - VASIL GORANOV

Vasil

Goranov is a contemporary painter from Bulgaria. He was born in

Velingrad in 1972 and studied at Veliko Tarnovo University.

His works are present in many international exhibitions and enjoy the appreciation of both critics and art lovers.

You will understand why after looking at some of his paintings:

Friday, November 20, 2020

HEALTH AND MEDICINAL BENEFITS OF RAISINS

Wednesday, November 18, 2020

NATURE'S WHISPER - by Aufie Zophy

LOVE AND BEAUTY - by Aufie Zophy

Monday, November 16, 2020

LEISURE - by W. H. Davies

|

A PSALM OF LIFE - by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

|

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)