Towards the hour of

supper on Friday, the twenty-sixth day of the month of December, a

little shepherd lad came into Nazareth, crying bitterly.

Some peasants, who

were drinking ale in the Blue Lion, opened the shutters to look into the

village orchard, and saw the child running over the snow. They

recognized him as the son of Korneliz, and called from the window: "What

is the matter? It's time you were abed!"

But, sobbing still

and shaking with terror, the boy cried that the Spaniards had come, that

they had set fire to the farm, had hanged his mother among the nut

trees and bound his nine little sisters to the trunk of a big tree. At

this the peasants rushed out of the inn. Surrounding the child, they

stunned him with their questionings and outcries. Between his sobs, he

added that the soldiers were on horseback and wore armor, that they had

taken away the cattle of his uncle, Petrus Krayer, and would soon be in

the forest with the sheep and cows. All now ran to the Golden Swan

where, as they knew, Korneliz and his brother-in-law were also drinking

their mug of ale. The moment the innkeeper heard these terrifying

tidings, he hurried into the village, crying that the Spaniards were at

hand.

What a stir, what an

uproar there was then in Nazareth! Women opened windows, and peasants

hurriedly left their houses carrying lights which were put out when they

reached the orchard, where, because of the snow and the full moon, one

could see as well as at midday.

Later, they gathered

round Korneliz and Krayer, in the open space which faced the inns.

Several of them had brought pitchforks and rakes, and consulted

together, terror-stricken, under the trees.

But, as they did not

know what to do, one of them ran to fetch the cure, who owned

Korneliz's farm. He came out of the house with the sacristan carrying

the keys of the church. All followed him into the churchyard, whither

his cry came to them from the top of the tower, that he beheld nothing

either in the fields, or by the forest, but that around the farm he saw

ominous red clouds, for all that the sky was of a deep blue and agleam

with stars over the rest of the plain.

After taking counsel

for a long time in the churchyard, they decided to hide in the wood

through which the Spaniards must pass, and, if these were not too

numerous, to attack them and recover Petrus Krayer's cattle and the

plunder which had been taken from the farm.

Having armed

themselves with pitchforks and spades, while the women remained outside

the church with the cure, they sought a suitable ambuscade. Approaching a

mill on a rising ground adjacent to the verge of the forest, they saw

the light of the burning farm flaming against the stars. There they

waited under enormous oaks, before a frozen mere.

A shepherd, known as

Red Dwarf, climbed the hill to warn the miller, who had stopped his

mill when he saw the flames on the horizon. He bade the peasant enter,

and both men went to a window to stare out into the night.

Before them the moon

shone over the burning farmstead, and in its light they saw a long

procession winding athwart the snow. Having carefully scrutinized it,

the Dwarf descended where his comrades waited under the trees, and now,

they too gradually distinguished four men on horseback behind a flock

which moved grazing on the plain.

While the peasants

in their blue breeches and red cloaks continued to search about the

margins of the mere and under the snowlit trees, the sacristan pointed

out to them a box-hedge, behind which they hid.

The Spaniards,

driving before them the sheep and the cattle, advanced upon the ice.

When the sheep reached the hedge they began to nibble at the green

stuff, and now Korneliz broke from the shadows of the bushes, followed

by the others with their pitchforks. Then in the midst of the huddled-up

sheep and of the cows who stared affrighted, the savage strife was

fought out beneath the moon, and ended in a massacre.

When they had slain

not only the Spaniards, but also their horses, Korneliz rushed thence

across the meadow in the direction of the flames, while the others

plundered and stripped the dead. Thereafter all returned to the village

with their flocks. The women, who were observing the dark forest from

behind the churchyard walls, saw them coming through the trees and ran

with the cure to meet them, and all returned dancing joyously amid the

laughter of the children and the barking of the dogs.

But, while they made

merry, under the pear trees of the orchard, where the Red Dwarf had

hung lanterns in honor of the kermesse, they anxiously demanded of the

cure what was to be done.

The outcome of this

was the harnessing of a horse to a cart in order to fetch the bodies of

the woman and the nine little girls to the village. The sisters and

other relations of the dead woman got into the cart along with the cure,

who, being old and very fat, could not walk so far.

In silence they

entered the forest, and emerged upon the moonlit plain. There, in the

white light, they descried the dead men, rigid and naked, among the

slain horses. Then they moved onward toward the farm, which still burned

in the midst of the plain.

When they came to

the orchard of the flaming house, they stopped at the gate of the

garden, dumb before the overwhelming misfortune of the peasant. For

there, his wife hung, quite naked, on the branches of an enormous nut

tree, among which he himself was now mounting on a ladder, and beneath

which, on the frozen grass, lay his nine little daughters. Korneliz had

already, climbed along the vast boughs, when suddenly, by the light of

the snow, he saw the crowd who horror-struck watched his every movement.

With tears in his eyes, he made a sign to them to help him, whereat the

innkeepers of the Blue Lion and the Golden Sun, the cure, with a

lantern, and many others, climbed up in the moonshine amid the

snow-laden branches, to unfasten the dead. The women of the village

received the corpse in their arms at the foot of the tree; even as our

Lord Jesus Christ was received by the women at the foot of the Cross.

On the morrow they buried her, and for the week thereafter nothing unusual happened in Nazareth.

But the following

Sunday, hungry wolves ran through the village after high mass, and it

snowed until midday. Then, suddenly, the sun shone brilliantly, and the

peasants went to dine as was their wont, and dressed for the

benediction.

There was no one to

be seen on the Place, for it froze bitterly. Only the dogs and chickens

roamed about under the trees, or the sheep nibbled at a three-cornered

bit of grass, while the cure's servant swept away the snow from his

garden.

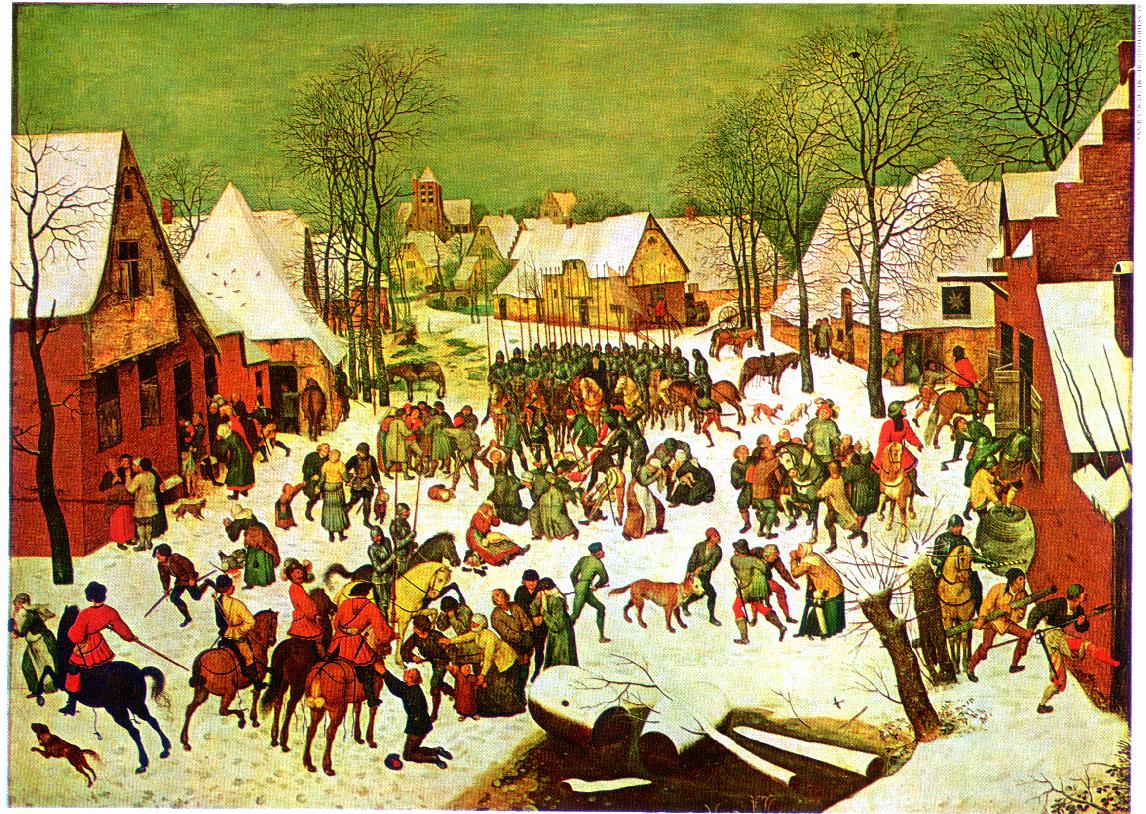

At that moment a

troop of armed men crossed the stone bridge at the end of the village,

and halted in the orchard. Peasants hurried from their houses, but,

recognizing the new-comers as Spaniards, they retreated terrified, and

went to the windows to see what would happen.

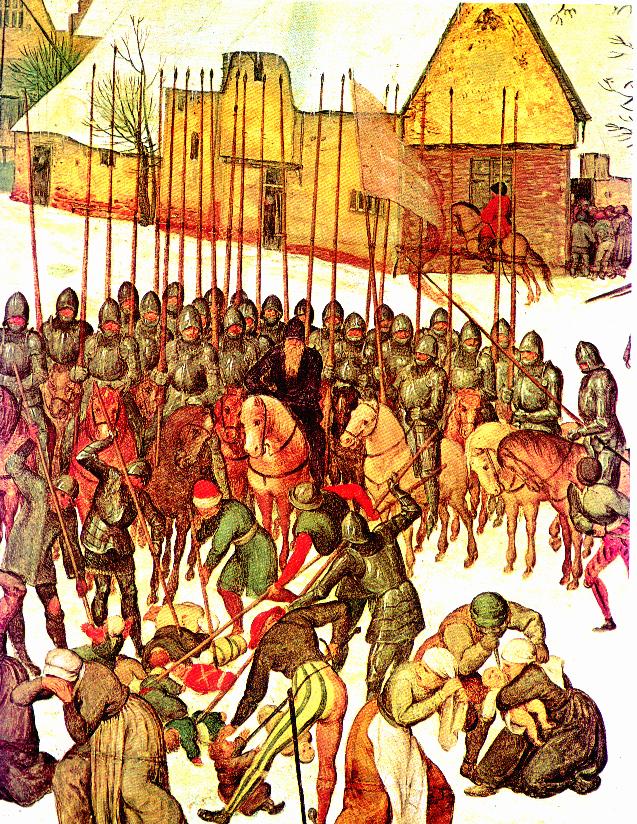

About thirty

soldiers, in full armor, surrounded an old man with a white beard.

Behind them, on pillions, rode red and yellow lancers who jumped down

and ran over the snow to shake off their stiffness, while several of the

soldiers in armor dismounted likewise and fastened their horses to the

trees.

Then they moved in

the direction of the Golden Sun, and knocked at the door. It was opened

reluctantly; the soldiers went in, warmed themselves near the fire, and

called for ale.

Presently they came

out of the inn, carrying pots, jugs, and rye-bread for their companions,

who surrounded the man with the white beard, where he waited behind the

hedge of lances.

As the street

remained deserted the commander sent some horsemen to the back of the

houses, to guard the village on the country side. He then ordered the

lancers to bring him all the children of two years old and under, to be

massacred, as is written in the Gospel of St. Matthew.

The soldiers first

went to the little inn of the Green Cabbage, and to the barber's cottage

which stood side by side midway in the street.

One of them opened a

sty and a litter of pigs wandered into the village. The innkeeper and

the barber came out, and humbly asked the men what they wanted; but they

did not understand Flemish, and went into the houses to look for the

children.

The innkeeper had

one child, who, in its little shift, was screaming on the table where

they had just dined. A soldier took it in his arms, and carried it away

under the apple trees, while the father and mother followed, crying.

Thereafter the

lancers opened other stable doors,—those of the cooper, the blacksmith,

the cobbler, and calves, cows, asses, pigs, goats, and sheep roamed

about the square. When they broke the carpenter's windows, several of

the oldest and richest inhabitants of the village assembled in the

street, and went to meet the Spaniards. Respectfully they took off their

caps and hats to the leader in the velvet mantle, and asked him what he

was going to do. He did not, understand their language; so some one ran

to fetch the cure.

The priest was

putting on a gold chasuble in the vestry, in readiness for the

benediction. The peasant cried: "The Spaniards are in the orchard!"

Horrified, the cure ran to the door of the church, and the choir-boys

followed, carrying wax-tapers and censer.

As he stood there,

he saw the animals from the pens and stables wandering on the snow and

on the grass; the horsemen in the village, the soldiers before the

doors, horses tied to trees all along the street; men and women

entreating the man who held the child in its little shift.

The cure hastened

into the churchyard, and the peasants turned anxiously towards him as he

came through the pear trees, like the Divine Presence itself robed in

white and gold. They crowded about him where he confronted the man with

the white beard.

He spoke in Flemish and in Latin, but the commander merely shrugged his shoulders to show that he did not understand.

The villagers asked

their priest in a low voice: "What does he say? What is he going to do?"

Others, when they saw the cure in the orchard, came cautiously from

their cottages, women hurried up and whispered in groups, while the

soldiers, till that moment besieging an inn, ran back at sight of the

crowd in the square.

Then the man who held the innkeeper's child by the leg cut off its head with his sword.

The people saw the

head fall, and thereafter the body lie bleeding upon the grass. The

mother picked it up, and carried it away, but forgot the head. She ran

towards her home, but stumbling against a tree fell prone on the snow,

where she lay in a swoon, while the father struggled between two

soldiers.

Some young peasants

cast stones and blocks of wood at the Spaniards, but the horsemen all

lowered their lances; the women fled and the cure with his parishioners

began to shriek with horror, amid the bleating of the sheep, the

cackling of the geese, and the barking of the dogs.

But as the soldiers moved away again into the street, the crowd stood silent to see what would happen.

A troop entered the

shop kept by the sacristan's sisters, but came out quietly, without

harming the seven women, who knelt on the threshold praying.

From these they went

to the inn of St. Nicholas, which belonged to the Hunchback. Here, too,

so as to appease them, the door was opened at once; but, when the

soldiers reappeared amid a great uproar, they carried three children in

their arms. The marauders were surrounded by the Hunchback, his wife,

and daughters, all, with clasped hands, imploring for mercy.

When the soldiers

came to their white-bearded leader, they placed the children at the foot

of an elm, where the little ones remained seated on the snow in their

Sunday clothes. But one of them, in a yellow frock, got up and toddled

unsteadily towards the sheep. A soldier followed, with bare sword; and

the child died with his face in the grass, while the others were killed

around the tree.

The peasants and the

innkeeper's daughters all fled screaming, and shut themselves up in

their houses. The cure, who was left alone in the orchard, threw himself

on his knees, first before one horseman, then another, and with crossed

arms, supplicated the Spaniards piteously, while the fathers and

mothers seated on the snow beyond wept bitterly for the dead children

whom they held upon their knees.

As the lancers

passed along the street, they noticed a big blue farmstead. When they

had tried, in vain, to force open the oaken door studded with nails,

they clambered atop of some tubs, which were frozen over near the

threshold, and by this means gained the house through the upper windows.

There had been a

kermesse in this farm. At sound of the broken window-panes, the families

who had assembled there to eat gaufres, custards, and hams, crowded

together behind the table on which still stood some empty jugs and

dishes. The soldiers entered the kitchen, and after savage struggle in

which many were wounded, they seized all the little boys and girls;

then, with these, and the servant who had bitten a lancer's thumb, they

left the house and fastened the door behind them in such a way that the

parents could not get out.

Thereafter the

lancers opened other stable doors,—those of the cooper, the blacksmith,

the cobbler, and calves, cows, asses, pigs, goats, and sheep roamed

about the square. When they broke the carpenter's windows, several of

the oldest and richest inhabitants of the village assembled in the

street, and went to meet the Spaniards. Respectfully they took off their

caps and hats to the leader in the velvet mantle, and asked him what he

was going to do. He did not, understand their language; so some one ran

to fetch the cure.

The priest was

putting on a gold chasuble in the vestry, in readiness for the

benediction. The peasant cried: "The Spaniards are in the orchard!"

Horrified, the cure ran to the door of the church, and the choir-boys

followed, carrying wax-tapers and censer.

As he stood there,

he saw the animals from the pens and stables wandering on the snow and

on the grass; the horsemen in the village, the soldiers before the

doors, horses tied to trees all along the street; men and women

entreating the man who held the child in its little shift.

The cure hastened

into the churchyard, and the peasants turned anxiously towards him as he

came through the pear trees, like the Divine Presence itself robed in

white and gold. They crowded about him where he confronted the man with

the white beard.

He spoke in Flemish and in Latin, but the commander merely shrugged his shoulders to show that he did not understand.

The villagers asked

their priest in a low voice: "What does he say? What is he going to do?"

Others, when they saw the cure in the orchard, came cautiously from

their cottages, women hurried up and whispered in groups, while the

soldiers, till that moment besieging an inn, ran back at sight of the

crowd in the square.

Then the man who held the innkeeper's child by the leg cut off its head with his sword.

The people saw the

head fall, and thereafter the body lie bleeding upon the grass. The

mother picked it up, and carried it away, but forgot the head. She ran

towards her home, but stumbling against a tree fell prone on the snow,

where she lay in a swoon, while the father struggled between two

soldiers.

Some young peasants

cast stones and blocks of wood at the Spaniards, but the horsemen all

lowered their lances; the women fled and the cure with his parishioners

began to shriek with horror, amid the bleating of the sheep, the

cackling of the geese, and the barking of the dogs.

But as the soldiers moved away again into the street, the crowd stood silent to see what would happen.

A troop entered the

shop kept by the sacristan's sisters, but came out quietly, without

harming the seven women, who knelt on the threshold praying.

From these they went

to the inn of St. Nicholas, which belonged to the Hunchback. Here, too,

so as to appease them, the door was opened at once; but, when the

soldiers reappeared amid a great uproar, they carried three children in

their arms. The marauders were surrounded by the Hunchback, his wife,

and daughters, all, with clasped hands, imploring for mercy.

When the soldiers

came to their white-bearded leader, they placed the children at the foot

of an elm, where the little ones remained seated on the snow in their

Sunday clothes. But one of them, in a yellow frock, got up and toddled

unsteadily towards the sheep. A soldier followed, with bare sword; and

the child died with his face in the grass, while the others were killed

around the tree.

The peasants and the

innkeeper's daughters all fled screaming, and shut themselves up in

their houses. The cure, who was left alone in the orchard, threw himself

on his knees, first before one horseman, then another, and with crossed

arms, supplicated the Spaniards piteously, while the fathers and

mothers seated on the snow beyond wept bitterly for the dead children

whom they held upon their knees.

As the lancers

passed along the street, they noticed a big blue farmstead. When they

had tried, in vain, to force open the oaken door studded with nails,

they clambered atop of some tubs, which were frozen over near the

threshold, and by this means gained the house through the upper windows.

There had been a

kermesse in this farm. At sound of the broken window-panes, the families

who had assembled there to eat gaufres, custards, and hams, crowded

together behind the table on which still stood some empty jugs and

dishes. The soldiers entered the kitchen, and after savage struggle in

which many were wounded, they seized all the little boys and girls;

then, with these, and the servant who had bitten a lancer's thumb, they

left the house and fastened the door behind them in such a way that the

parents could not get out.

The villagers who

had no children slowly left their houses, and followed the soldiers at a

distance. They saw them throw down their victims on the grass before

the old man, and callously kill them with lance and sword. During this,

men and women leaned out of all the windows of the blue house, and out

of the barn, blaspheming and flinging their hands to heaven, when they

saw the red, pink, and white frocks of their motionless little ones on

the grass between the trees. The soldiers next hanged the farm servant

at the sign of the Half Moon on the other side of the street, and there

was a long silence in the village.

The massacre now

became general. Mothers fled from their houses, and attempted to escape

through the flower and vegetable gardens, and so into the country

beyond, but the horsemen pursued them and drove them back into the

street. Peasants with caps in their clasped hands knelt before the men

who dragged away their children, while amid the confusion the dogs

barked joyously. The cure, with hands upraised to heaven, rushed up and

down in front of the houses and under the trees, praying desperately;

here and there, soldiers, trembling with cold, blew on their fingers as

they moved about the road, or waited with hands in their breeches

pockets, and swords under their arms, before the windows of the houses

which were being scaled.

Everywhere, as in

small bands of twos and threes, they moved along the streets, where

these scenes were being enacted, and entered the houses, they beheld the

piteous grief of the peasants. The wife of a market-gardener, who

occupied a red brick cottage near the church, pursued with a wooden

stool the two men who carried off her children in a wheelbarrow. When

she saw them die, a horrible sickness came upon her, and they thrust her

down on the stool under a tree by the roadside.

Other soldiers

swarmed up the lime trees in front of a farmstead with its blank walls

tinted mauve, and entered the house by removing the tiles. When they

came back on to the roof, the father and mother, with outstretched arms,

tried to follow them through the opening, but the soldiers repeatedly

pushed them back, and had at last to strike them on the head with their

swords, before they could disengage themselves and regain the street.

One family shut up

in the cellar of a large cottage lamented near the grating, through

which the father wildly brandished a pitchfork. Outside on a heap of

manure, a bald old man sobbed all alone; in the square, a woman in a

yellow dress had swooned, and her weeping husband now supported her

under the arms, against a pear tree; another woman in red fondled her

little girl, bereft of her hands, and lifted now one tiny arm, now the

other, to see if the child would not move. Yet another woman fled

towards the country; but the soldiers pursued her among the hayricks,

which stood out in black relief against the fields of snow.

Beneath the inn of

the Four Sons of Aymon a surging tumult reigned. The inhabitants had

formed a barricade, and the soldiers went round and round the house

without being able to enter. Then they were attempting to climb up to

the signboard by the creepers, when they noticed a ladder behind the

garden door. This they raised against the wall, and went up it in file.

But the innkeeper and all his family hurled tables, stools, plates, and

cradles down upon them from the windows; the ladder was overturned, and

the soldiers fell.

In a wooden hut at

the end of the village, another band found a peasant woman washing her

children in a tub near the fire. Being old and very deaf, she did not

hear them enter. Two men took the tub and carried it away, and the

stupefied woman followed with the clothes in which she was about to

dress the children. But when she saw traces of blood everywhere in the

village, swords in the orchards, cradles overturned in the street, women

on their knees, others who wrung their hands over the dead, she began

to scream and beat the soldiers, who put down the tub to defend

themselves. The cure hastened up also, and with hands clasped over his

chasuble, entreated the Spaniards before the naked little ones howling

in the water. Some soldiers came up, tied the mad peasant to a tree, and

carried off the children.

The butcher, who had

hidden his little girl, leaned against his shop, and looked on

callously. A lancer and one of the men in armor entered the house and

found the child in a copper boiler. Then the butcher in despair took one

of his knives and rushed after them into the street, but soldiers who

were passing disarmed him and hanged him by the hands to the hooks in

the wall—there, among the flayed animals, he kicked and struggled,

blaspheming, until the evening.

Near the churchyard,

there was a great gathering before a long, low house, painted green.

The owner, standing on his threshold, shed bitter tears; as he was very

fat and jovial looking, he excited the pity of some soldiers who were

seated in the sun against the wall, patting a dog. The one, too, who

dragged away his child by the hand, gesticulated as if to say: "What can

I do? It's not my fault!"

A peasant who was

pursued, jumped into a boat, moored near the stone bridge, and with his

wife and children moved away across the unfrozen part of the narrow

lagoon. Not daring to follow, the soldiers strode furiously through the

reeds. They climbed up into the willows on the banks to try to reach the

fugitives with their lances—as they did not succeed, they continued for

a long time to threaten the terrified family adrift upon the black

water.

The orchard was

still full of people, for it was there, in front of the white-bearded

man who directed the massacre, that most of the children were killed.

Little dots who could just walk alone stood side by side munching their

slices of bread and jam, and stared curiously at the slaying of their

helpless playmates, or collected round the village fool who played his

flute on the grass.

Then suddenly there

was a uniform movement in the village. The peasants ran towards the

castle which stood on the brown rising ground, at the end of the street.

They had seen their seigneur leaning on the battlements of his tower

and watching the massacre. Men, women, old people, with hands

outstretched, supplicated to him, in his velvet mantle and his gold cap,

as to a king in heaven. But he raised his arms and shrugged his

shoulders to show his helplessness, and when they implored him more and

more persistently, kneeling in the snow, with bared heads, and uttering

piteous cries, he turned slowly into the tower and the peasants' last

hope was gone.

When all the

children were slain, the tired soldiers wiped their swords on the grass,

and supped under the pear trees. Then they mounted one behind the

other, and rode out of Nazareth across the stone bridge, by which they

had come.

The setting of the

sun behind the forest made the woods aflame, and dyed the village

blood-red. Exhausted with running and entreating, the cure had thrown

himself upon the snow, in front of the church, and his servant stood

near him. They stared upon the street and the orchard, both thronged

with the peasants in their best clothes. Before many thresholds, parents

with dead children on their knees bewailed with ever fresh amaze their

bitter grief. Others still lamented over the children where they had

died, near a barrel, under a barrow, or at the edge of a pool. Others

carried away the dead in silence. There were some who began to wash the

benches, the stools, the tables, the blood-stained shifts, and to pick

up the cradles which had been thrown into the street. Mother by mother

moaned under the trees over the dead bodies which lay upon the grass,

little mutilated bodies which they recognized by their woollen frocks.

Those who were childless moved aimlessly through the square, stopping at

times in front of the bereaved, who wailed and sobbed in their sorrow.

The men, who no longer wept, sullenly pursued their strayed animals,

around which the barking dogs coursed; or, in silence, repaired so far

their broken windows and rifled roofs. As the moon solemnly rose through

the quietudes of the sky, deep silence as of sleep descended upon the

village, where now not the shadow of a living thing stirred.

No comments:

Post a Comment