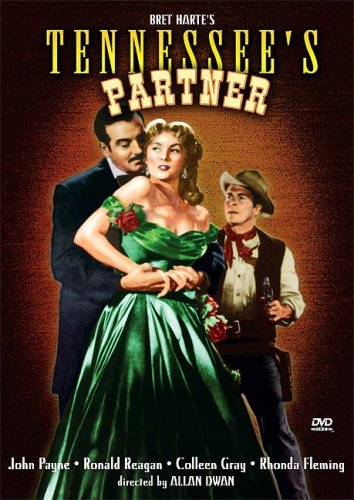

I do not think that we

ever knew his real name. Our ignorance of it certainly never gave us any

social inconvenience, for at Sandy Bar in 1854 most men were christened

anew. Sometimes these appellatives were derived from some

distinctiveness of dress, as in the case of “Dungaree Jack”; or from

some peculiarity of habit, as shown in “Saleratus Bill,” so called from

an undue proportion of that chemical in his daily bread; or for some

unlucky slip, as exhibited in “The Iron Pirate,” a mild, inoffensive

man, who earned that baleful title by his unfortunate mispronunciation

of the term “iron pyrites.” Perhaps this may have been the beginning of a

rude heraldry; but I am constrained to think that it was because a

man's real name in that day rested solely upon his own unsupported

statement. “Call yourself Clifford, do you ?” said Boston, addressing a

timid newcomer with infinite scorn; “hell is full of such Cliffords !”

He then introduced the unfortunate man, whose name happened to be really

Clifford, as “Jay-bird Charley” - an unhallowed inspiration of the

moment that clung to him ever after.

But to return to

Tennessee's Partner, whom we never knew by any other than this relative

title; that he had ever existed as a separate and distinct individuality

we only learned later. It seems that in 1853 he left Poker Flat to go

to San Francisco, ostensibly to procure a wife. He never got any farther

than Stockton. At that place he was attracted by a young person who

waited upon the table at the hotel where he took his meals. One morning

he said something to her which caused her to smile not unkindly, to

somewhat coquettishly break a plate of toast over his upturned, serious,

simple face, and to retreat to the kitchen. He followed her, and

emerged a few moments later, covered with more toast and victory. That

day week they were married by a justice of the peace, and returned to

Poker Flat. I am aware that something more might be made of this

episode, but I prefer to tell it as it was current at Sandy Bar - in the

gulches and barrooms - where all sentiment was modified by a strong

sense of humor.

Of their married

felicity but little is known, perhaps for the reason that Tennessee,

then living with his Partner, one day took occasion to say something to

the bride on his own account, at which, it is said, she smiled not

unkindly and chastely retreated - this time as far as Marysville, where

Tennessee followed her, and where they went to housekeeping without the

aid of a justice of the peace. Tennessee's Partner took the loss of his

wife simply and seriously, as was his fashion. But to everybody's

surprise, when Tennessee one day returned from Marysville, without his

Partner's wife, she having smiled and retreated with somebody else,

Tennessee's Partner was the first man to shake his hand and greet him

with affection. The boys who had gathered in the canyon to see the

shooting were naturally indignant. Their indignation might have found

vent in sarcasm but for a certain look in Tennessee's Partner's eye that

indicated a lack of humorous appreciation. In fact, he was a grave man,

with a steady application to practical detail which was unpleasant in a

difficulty.

Meanwhile a popular feeling

against Tennessee had grown up on the Bar. He was known to be a

gambler; he was suspected to be a thief. In these suspicions Tennessee's

Partner was equally compromised; his continued intimacy with Tennessee

after the affair above quoted could only be accounted for on the

hypothesis of a copartnership of crime. At last Tennessee's guilt became

flagrant. One day he overtook a stranger on his way to Red Dog. The

stranger afterward related that Tennessee beguiled the time with

interesting anecdote and reminiscence, but illogically concluded the

interview in the following words: “And now, young man, I'll trouble you

for your knife, your pistols, and your money. You see your weppings

might get you into trouble at Red Dog, and your money's a temptation to

the evilly disposed. I think you said your address was San Francisco. I

shall endeavor to call.” It may be stated here that Tennessee had a fine

flow of humor, which no business preoccupation could wholly subdue.

This exploit was his last.

Red Dog and Sandy Bar made common cause against the highwayman.

Tennessee was hunted in very much the same fashion as his prototype, the

grizzly. As the toils closed around him, he made a desperate dash

through the Bar, emptying his revolver at the crowd before the Arcade

Saloon, and so on up Grizzly Canyon; but at its farther extremity he was

stopped by a small man on a gray horse. The men looked at each other a

moment in silence. Both were fearless, both self-possessed and

independent; and both types of a civilization that in the seventeenth

century would have been called heroic, but, in the nineteenth, simply

“reckless.” “What have you got there? - I call,” said Tennessee,

quietly. “Two bowers and an ace,” said the stranger, as quietly, showing

two revolvers and a bowie knife. “That takes me,” returned Tennessee;

and with this gamblers' epigram, he threw away his useless pistol, and

rode back with his captor.

It was a warm night. The

cool breeze which usually sprang up with the going down of the sun

behind the chaparral crested mountain was that evening withheld from

Sandy Bar. The little canyon was stifling with heated resinous odors,

and the decaying driftwood on the Bar sent forth faint, sickening

exhalations. The feverishness of day, and its fierce passions, still

filled the camp. Lights moved restlessly along the bank of the river,

striking no answering reflection from its tawny current. Against the

blackness of the pines the windows of the old loft above the express

office stood out staringly bright; and through their curtainless panes

the loungers below could see the forms of those who were even then

deciding the fate of Tennessee. And above all this, etched on the dark

firmament, rose the Sierra, remote and passionless, crowned with remoter

passionless stars.

The trial of Tennessee was

conducted as fairly as was consistent with a judge and jury who felt

themselves to some extent obliged to justify, in their verdict, the

previous irregularities of arrest and indictment. The law of Sandy Bar

was implacable, but not vengeful. The excitement and personal feeling of

the chase were over; with Tennessee safe in their hands they were ready

to listen patiently to any defense, which they were already satisfied

was insufficient. There being no doubt in their own minds, they were

willing to give the prisoner the benefit of any that might exist. Secure

in the hypothesis that he ought to be hanged, on general principles,

they indulged him with more latitude of defense than his reckless

hardihood seemed to ask. The Judge appeared to be more anxious than the

prisoner, who, otherwise unconcerned, evidently took a grim pleasure in

the responsibility he had created. “I don't take any hand in this yer

game,” had been his invariable but good humored reply to all questions.

The Judge, who was also his captor for a moment vaguely regretted that

he had not shot him “on sight” that morning, but presently dismissed

this human weakness as unworthy of the judicial mind. Nevertheless, when

there was a tap at the door, and it was said that Tennessee's Partner

was there on behalf of the prisoner, he was admitted at once without

question. Perhaps the younger members of the jury, to whom the

proceedings were becoming irksomely thoughtful, hailed him as a relief.

For he was not, certainly,

an imposing figure. Short and stout, with a square face sunburned into a

preternatural redness, clad in a loose duck “jumper” and trousers

streaked and splashed with red soil, his aspect under any circumstances

would have been quaint, and was now even ridiculous. As he stooped to

deposit at his feet a heavy carpetbag he was carrying, it became

obvious, from partially developed legends and inscriptions, that the

material with which his trousers had been patched had been originally

intended for a less ambitious covering. Yet he advanced with great

gravity, and after having shaken the hand of each person in the room

with labored cordiality, he wiped his serious, perplexed face on a red

bandanna handkerchief, a shade lighter than his complexion, laid his

powerful hand upon the table to steady himself, and thus addressed the

Judge:

“I was passin' by,” he

began, by way of apology, “and I thought I'd just step in and see how

things was gittin' on with Tennessee thar my pardner. It's a hot night. I

disremember any sich weather before on the Bar.”

He paused a moment, but

nobody volunteering any other meteorological recollection, he again had

recourse to his pocket handkerchief, and for some moments mopped his

face diligently.

“Have you anything to say in behalf of the prisoner?” said the Judge, finally.

“Thet's it,” said

Tennessee's Partner, in a tone of relief. “I come yar as Tennessee's

pardner knowing him nigh on four year, off and on, wet and dry, in luck

and out o' luck. His ways ain't allers my ways, but thar ain't any

p'ints in that young man, thar ain't any liveliness as he's been up to,

as I don't know. And you sez to me, sez you confidential-like, and

between man and man sez you, 'Do you know anything in his behalf?' and I

sez to you, sez I confidential-like, as between man and man - 'What

should a man know of his pardner ?'”

“Is this all you have to

say?” asked the Judge impatiently, feeling, perhaps, that a dangerous

sympathy of humor was beginning to humanize the Court.

“Thet's so,” continued

Tennessee's Partner. “It ain't for me to say anything agin' him. And

now, what's the case? Here's Tennessee wants money, wants it bad, and

doesn't like to ask it of his old pardner. Well, what does Tennessee do ?

He lays for a stranger, and he fetches that stranger. And you lays for

HIM, and you fetches HIM; and the honors is easy. And I put it to you,

bein' a far-minded man, and to you, gentlemen, all, as far-minded men,

ef this isn't so.”

“Prisoner,” said the Judge, interrupting, “have you any questions to ask this man ?”

“No! no!” continued

Tennessee's Partner, hastily. “I play this yer hand alone. To come down

to the bedrock, it's just this: Tennessee, thar, has played it pretty

rough and expensive-like on a stranger, and on this yer camp. And now,

what's the fair thing? Some would say more; some would say less. Here's

seventeen hundred dollars in coarse gold and a watch - it's about all my

pile - and call it square !” And before a hand could be raised to

prevent him, he had emptied the contents of the carpetbag upon the

table.

For a moment his life was

in jeopardy. One or two men sprang to their feet, several hands groped

for hidden weapons, and a suggestion to “throw him from the window” was

only overridden by a gesture from the Judge. Tennessee laughed. And

apparently oblivious of the excitement, Tennessee's Partner improved the

opportunity to mop his face again with his handkerchief.

When order was restored,

and the man was made to understand, by the use of forcible figures and

rhetoric, that Tennessee's offense could not be condoned by money, his

face took a more serious and sanguinary hue, and those who were nearest

to him noticed that his rough hand trembled slightly on the table. He

hesitated a moment as he slowly returned the gold to the carpetbag, as

if he had not yet entirely caught the elevated sense of justice which

swayed the tribunal, and was perplexed with the belief that he had not

offered enough. Then he turned to the Judge, and saying, “This yer is a

lone hand, played alone, and without my pardner,” he bowed to the jury

and was about to withdraw when the Judge called him back. “If you have

anything to say to Tennessee, you had better say it now.” For the first

time that evening the eyes of the prisoner and his strange advocate met.

Tennessee smiled, showed his white teeth, and, saying, “Euchred, old

man!” held out his hand. Tennessee's Partner took it in his own, and

saying, “I just dropped in as I was passin' to see how things was

gettin' on,” let the hand passively fall, and adding that it was a warm

night, again mopped his face with his handkerchief, and without another

word withdrew.

The two men never again met

each other alive. For the unparalleled insult of a bribe offered to

Judge Lynch who, whether bigoted, weak, or narrow, was at least

incorruptible firmly fixed in the mind of that mythical personage any

wavering determination of Tennessee's fate; and at the break of day he

was marched, closely guarded, to meet it at the top of Marley's Hill.

How he met it, how cool he

was, how he refused to say anything, how perfect were the arrangements

of the committee, were all duly reported, with the addition of a warning

moral and example to all future evildoers, in the RED DOG CLARION, by

its editor, who was present, and to whose vigorous English I cheerfully

refer the reader. But the beauty of that midsummer morning, the blessed

amity of earth and air and sky, the awakened life of the free woods and

hills, the joyous renewal and promise of Nature, and above all, the

infinite Serenity that thrilled through each, was not reported, as not

being a part of the social lesson. And yet, when the weak and foolish

deed was done, and a life, with its possibilities and responsibilities,

had passed out of the misshapen thing that dangled between earth and

sky, the birds sang, the flowers bloomed, the sun shone, as cheerily as

before; and possibly the RED DOG CLARION was right.

Tennessee's Partner was not

in the group that surrounded the ominous tree. But as they turned to

disperse attention was drawn to the singular appearance of a motionless

donkey cart halted at the side of the road. As they approached, they at

once recognized the venerable “Jenny” and the two wheeled cart as the

property of Tennessee's Partner used by him in carrying dirt from his

claim; and a few paces distant the owner of the equipage himself,

sitting under a buckeye tree, wiping the perspiration from his glowing

face. In answer to an inquiry, he said he had come for the body of the

“diseased,” “if it was all the same to the committee.” He didn't wish to

“hurry anything”; he could “wait.” He was not working that day; and

when the gentlemen were done with the “diseased,” he would take him. “Ef

thar is any present,” he added, in his simple, serious way, “as would

care to jine in the fun'l, they kin come.” Perhaps it was from a sense

of humor, which I have already intimated was a feature of Sandy Bar

perhaps it was from something even better than that; but two-thirds of

the loungers accepted the invitation at once.

It was noon when the body

of Tennessee was delivered into the hands of his Partner. As the cart

drew up to the fatal tree, we noticed that it contained a rough, oblong

box apparently made from a section of sluicing and half-filled with bark

and the tassels of pine. The cart was further decorated with slips of

willow, and made fragrant with buckeye blossoms. When the body was

deposited in the box, Tennessee's Partner drew over it a piece of tarred

canvas, and gravely mounting the narrow seat in front, with his feet

upon the shafts, urged the little donkey forward. The equipage moved

slowly on, at that decorous pace which was habitual with “Jenny” even

under less solemn circumstances. The men half curiously, half jestingly,

but all good-humoredly strolled along beside the cart; some in advance,

some a little in the rear of the homely catafalque. But, whether from

the narrowing of the road or some present sense of decorum, as the cart

passed on, the company fell to the rear in couples, keeping step, and

otherwise assuming the external show of a formal procession. Jack

Folinsbee, who had at the outset played a funeral march in dumb show

upon an imaginary trombone, desisted, from a lack of sympathy and

appreciation not having, perhaps, your true humorist's capacity to be

content with the enjoyment of his own fun.

The way led through Grizzly Canyon by this time clothed in funereal

drapery and shadows. The redwoods, burying their moccasined feet in the

red soil, stood in Indian file along the track, trailing an uncouth

benediction from their bending boughs upon the passing bier. A hare,

surprised into helpless inactivity, sat upright and pulsating in the

ferns by the roadside as the cortege went by. Squirrels hastened to gain

a secure outlook from higher boughs; and the bluejays, spreading their

wings, fluttered before them like outriders, until the outskirts of

Sandy Bar were reached, and the solitary cabin of Tennessee's Partner.

Viewed under more favorable circumstances, it would not have been a

cheerful place. The unpicturesque site, the rude and unlovely outlines,

the unsavory details, which distinguish the nest-building of the

California miner, were all here, with the dreariness of decay

superadded. A few paces from the cabin there was a rough enclosure,

which in the brief days of Tennessee's Partner's matrimonial felicity

had been used as a garden, but was now overgrown with fern. As we

approached it we were surprised to find that what we had taken for a

recent attempt at cultivation was the broken soil about an open grave.

The cart was halted before the enclosure; and rejecting the offers

of assistance with the same air of simple self-reliance he had displayed

throughout, Tennessee's Partner lifted the rough coffin on his back and

deposited it, unaided, within the shallow grave. He then nailed down

the board which served as a lid; and mounting the little mound of earth

beside it, took off his hat, and slowly mopped his face with his

handkerchief. This the crowd felt was a preliminary to speech; and they

disposed themselves variously on stumps and boulders, and sat expectant.

“When a man,” began Tennessee's Partner, slowly, “has been running

free all day, what's the natural thing for him to do? Why, to come home.

And if he ain't in a condition to go home, what can his best friend do?

Why, bring him home! And here's Tennessee has been running free, and we

brings him home from his wandering.” He paused, and picked up a

fragment of quartz, rubbed it thoughtfully on his sleeve, and went on:

“It ain't the first time that I've packed him on my back, as you see'd

me now. It ain't the first time that I brought him to this yer cabin

when he couldn't help himself; it ain't the first time that I and

'Jinny' have waited for him on yon hill, and picked him up and so

fetched him home, when he couldn't speak, and didn't know me. And now

that it's the last time, why”—he paused and rubbed the quartz gently on

his sleeve “you see it's sort of rough on his pardner. And now,

gentlemen,” he added, abruptly, picking up his long-handled shovel, “the

fun'l's over; and my thanks, and Tennessee's thanks, to you for your

trouble.”

Resisting any proffers of assistance, he began to fill in the

grave, turning his back upon the crowd that after a few moments'

hesitation gradually withdrew. As they crossed the little ridge that hid

Sandy Bar from view, some, looking back, thought they could see

Tennessee's Partner, his work done, sitting upon the grave, his shovel

between his knees, and his face buried in his red bandanna handkerchief.

But it was argued by others that you couldn't tell his face from his

handkerchief at that distance; and this point remained undecided.

In the reaction that followed the feverish excitement of that day,

Tennessee's Partner was not forgotten. A secret investigation had

cleared him of any complicity in Tennessee's guilt, and left only a

suspicion of his general sanity. Sandy Bar made a point of calling on

him, and proffering various uncouth, but well-meant kindnesses. But from

that day his rude health and great strength seemed visibly to decline;

and when the rainy season fairly set in, and the tiny grass-blades were

beginning to peep from the rocky mound above Tennessee's grave, he took

to his bed. One night, when the pines beside the cabin were swaying in

the storm, and trailing their slender fingers over the roof, and the

roar and rush of the swollen river were heard below, Tennessee's Partner

lifted his head from the pillow, saying, “It is time to go for

Tennessee; I must put 'Jinny' in the cart”; and would have risen from

his bed but for the restraint of his attendant. Struggling, he still

pursued his singular fancy: “There, now, steady, 'Jinny' steady, old

girl. How dark it is! Look out for the ruts and look out for him, too,

old gal. Sometimes, you know, when he's blind-drunk, he drops down right

in the trail. Keep on straight up to the pine on the top of the hill.

Thar I told you so! thar he is coming this way, too all by himself,

sober, and his face a-shining. Tennessee ! Pardner !”

And so they met.

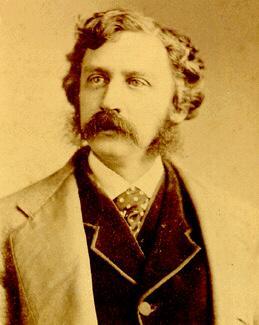

Bret

Harte (born Francis Brett Hart) - 1836 – 1902 was an American short

story writer and poet, best remembered for his short fiction featuring

miners, gamblers, and other romantic figures of the California Gold

Rush. In a career spanning more than four decades, he wrote poetry,

plays, lectures, book reviews, editorials, and magazine sketches in

addition to fiction.

As

he moved from California to the eastern U.S. to Europe, he incorporated

new subjects and characters into his stories, but his Gold Rush tales

have been the works most often reprinted, adapted, and admired.

No comments:

Post a Comment